#greenfield

On the Power of “No”

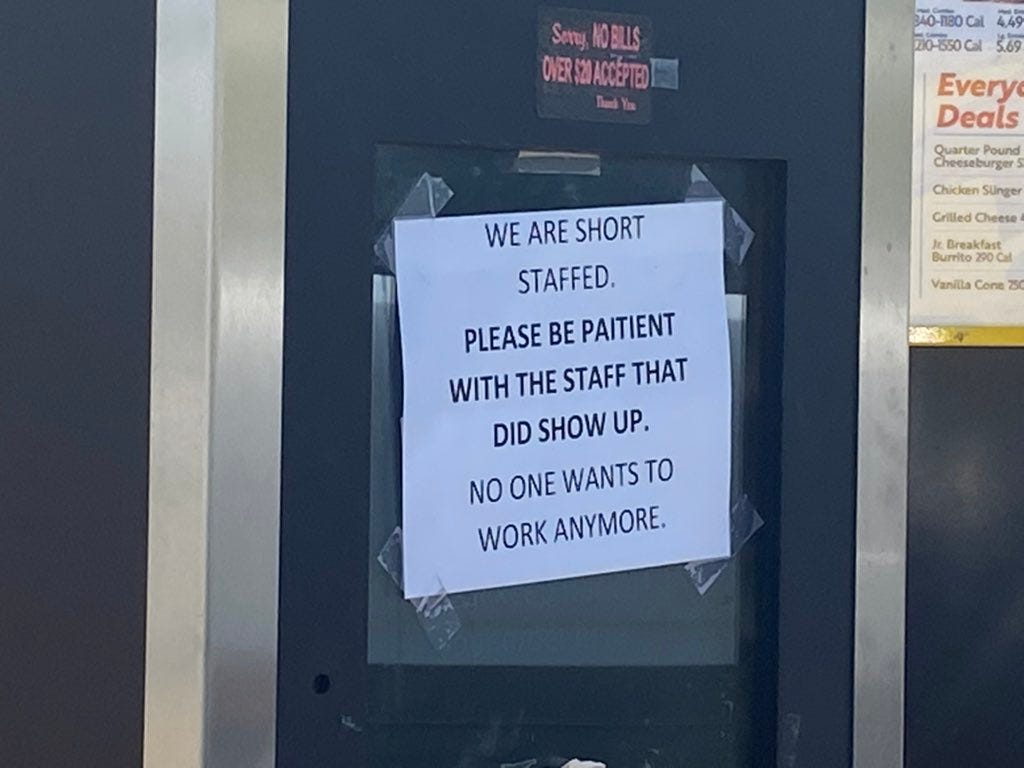

A friend writes: “The power to say ‘no’ is real power”, in the context of unemployment and other income alternatives giving workers the power to turn down oppressive employment conditions, see “The ‘Capitalism is Broken’ Economy”.

"No" in that context is BATNA, best alternative to negotiated agreement. Or as Humphrey Bogart piquantly put it, “fuck you money” — having sufficient saved resources to be able to turn down demeaning or objectionable work. Curiously, much of the labour-capital dynamic seems oriented at denying labour BATNA power.

“No” then is the only power, in many regards.

The concept appears as “power by veto” (literally, "I forbid"), or similar. It’s the notion that in any sufficiently complex group, power gravitates (for better or worse) to the individual or group with the power to prevent something from happening. The alternative of course being the power of individual enablement or execution --- a case where the power of "no" is internalised.

This has a number of consequences, some with positive connotations, some not.

- It manifests in the United Nations Security Council, where any of the five permanent members (US, UK, France, (now) Russia, and China can exercise a veto. There’s some interesting political science literature on this, beginning in the 1950s or so.

- It manifests in the US senate through various filibustering and process-halting powers.

- In manifests in the executive in many governments as the veto power.

- It manifests in real estate as NIMBYism. Or by approval review (a/k/a “removal-of-veto authority”).

- It’s the “dog in the manger” trope (dog in the feed trough prevents any other animals from feeding, though the dog itself doesn’t benefit).

- It’s the power of collective action exercised as a strike, blockade, scuttling, boycott, shunning, etc.

This is the key difference between greenfield land-development projects, in which there are no vested interests to block progress, vs. brownfield projects, with vested interests (or various forms if existing damage or harms which need to be remediated) that do. In particular, transport and infrastructure products in a greenfield occur where there are no or few counterveiling forces to oppose them, but by their own success create such forces which then tend to frustrate further or alternate development. Major transportation projects tend to occur either where significant economic development has not yet occurred, or in regions recently weakened by war or genocide. The initial industrialisation (and canal & rail transport network development) of Britain and China the first, and the high-speed rail networks development of France and Japan following World War II a case following devastation by war, and development of the American frontier of a post-genocide instance.

(Not all greenfields are free of impediments, but the ones that exist tend to be at least natural, inanimate, and nonpolitical, at root.)

Arguably, one could distinguish early-phase technological explorations where good effects either dominate over bad, or where bad effects are unknown (tying to my concept of #manifestation in the sense of known, apparent, communicable/expressable, or comprehensible), and late-phase technological developments in which costs, consequences, and risks are far more clear.

I’ve also had an idea that “no” is the word at which a child first expresses their own identity as distinct from the world, family, or tribe around them. You might argue that crying and anger are forms of “no”, and I’d grant that. But there are also linguistic and cognitive senses of “no” which become more developed with time (or at least that’s my experience).We mighti initially only reject requests or orders. With greater development, “no” applies to framings, models, social constructs, philosophies and religions, social and societal narratives, and more.

#no #veto #power #manifestation #greenfield #brownfield #infrastructure #transportation