One person like that

1 Shares

The field of space vehicle design is obsessed with efficiency by necessity. The cost to do anything in space is astronomical, and also heavily tied to launch weight. Thus, any technology or technique that can bring those figures down is prime for exploitation.

In recent years, mercury thrusters promised to be one such technology. The only catch was the potentially-ruinous environmental cost. Today, we'll look at the benefits of mercury thrusters, and how they came to be outlawed in short order.

As we've explored in our previous in-depth explainer, ion thrusters have proven valuable in innumerable space missions. Rather than using chemical reactions to generate thrust, they use electric fields to accelerate ions instead. Compared to traditional rockets, they can't generate anywhere near as much thrust. However, they are far more fuel-efficient. This means they can generate far more delta-v (change in velocity) with the same amount of fuel.

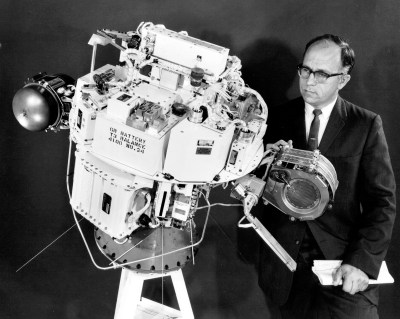

NASA experimented with mercury-based ion thrusters on the SERT-I (pictured) and SERT-II spacecraft. However, mercury was deemed too toxic to use in future missions. Credit: NASA, public domain

NASA experimented with mercury-based ion thrusters on the SERT-I (pictured) and SERT-II spacecraft. However, mercury was deemed too toxic to use in future missions. Credit: NASA, public domain

Although their thrust is so meagre that you could never use one to launch a vehicle into orbit, they find their primary application in stationkeeping for satellites, helping them maintain position over time against the forces of upper-atmospheric drag. They can also be used to propel long-range probes that don't have gravity to fight against.

These days, most thrusters use inert gases like xenon or krypton as fuel. However, these gases are expensive and their molecules are relatively lightweight. Mercury, on the other hand, is much heavier, still very easy to ionize, and easy to store on a spacecraft in liquid form. It's also very, very, cheap. By sheer virtue of its toxicity, many industries are often stuck paying to dispose of mercury as a byproduct. The old saying that " you can 't even give it away" really does apply here.

Mercury has a multitude of uses, such as the thermometer seen here. However, the silvery liquid metal is now used less often due to knowledge of its negative health effects. Credit: CambridgeBayWeather, public domain

Mercury has a multitude of uses, such as the thermometer seen here. However, the silvery liquid metal is now used less often due to knowledge of its negative health effects. Credit: CambridgeBayWeather, public domain

While mercury makes an excellent ion thruster fuel on paper, its toxicity is too potent to ignore. Causing deletrious effects to the nervous system and brain, its presence in the environment can have major negative effects on human populations. From lowering IQs to damaging memory, it's all bad all the way down. It's a toxin that accumulates in the body over time, and often enters the human body through the food chain. Indeed, mercury concentrations in many sea creatures mean that pregnant women are specifically advised to avoid many types of seafood.

For this reason, NASA abandoned the use of mercury as a propellant after initial experiments in the 1970s. Outside of contaminating the atmosphere, mercury comes with other risks too. There are occupational hazards for the crews working on the thrusters. Furthermore, explosions on the launchpad or crashes would spread the toxic material into the surrounding environment.

For these reasons, mercury was quickly considered a "dead fuel" by NASA, simply too dangerous to use despite the benefits.

NASA moved on to xenon-fuelled Hall effect thrusters after mercury was deemed too dangerous to use. Credit: NASA JPL, public domain

NASA moved on to xenon-fuelled Hall effect thrusters after mercury was deemed too dangerous to use. Credit: NASA JPL, public domain

As is so often the case, however, a Silicon Valley startup was reported to be "disrupting" an established industry by rehashing an old idea. Bloomberg ran a story in 2018, regarding the activities of startup Apollo Fusion. Industry insiders told the outlet that the startup was shopping around a new thruster technology using mercury as a propellant.

This quickly set alarm bells ringing for many around the world. With SpaceX planning to launch over 10,000 satellites over a period of a few years, and many other companies rushing to establish their own massive satellite fleets, prospects were terrifying. If Apollo Fusion got a contract to equip thousands of satellites with mercury thrusters, widespread pollution of the entire Earth was suddenly on the table.

A scientific paper showed that a constellation of 2,000 satellites with 100 kg of propellant on board would deposit 20,000 kg of mercury into the upper atmosphere each year for a decade. Due to the weight of mercury ions, the majority would end up falling back to Earth, and account for 1% of existing global mercury emissions. Modelling suggested 75% of this mercury would end up in the world's oceans, with negative impacts on marine life and fishing operations.

60 Starlink satellites seen prior to deployment in 2019.

60 Starlink satellites seen prior to deployment in 2019.

Concerns abounded that if mercury thrusters were used for upcoming constellations of thousands of satellites, it could spread significant pollution into the atmosphere and around the world. Credit: SpaceX, public domain

Great effort has been expended over the decades to reduce the amount of mercury in the environment. The Minimata Convention on Mercury, a treaty from the United Nations, provided a framework for controlling mercury use by signatory countries. 128 countries signed the treaty, involving restrictions on the use of mercury in everything from batteries to lamps, soaps, and cosmetics.

At the time of signing in 2013, the idea of a return to mercury propulsion simply wasn't on the table. Apollo Fusion wasn't established until 2016. Worse, US regulations meant that there was precious little stopping any company that wished to launch mercury into space. Communication satellites fall under the jurisdiction of the Federal Communications Commission, which allowed satellite operators to self-certify their craft as having no deleterious impacts on humans or the environment.

Thankfully, the hard work of scientists lobbying against the technology bore fruit. In March this year, the UN held a meeting regarding the Minamata Convention on Mercury, and adopted a resolution to phase out any use of mercury as a satellite propellant by 2025.

With most spacefaring nations being signatories to the convention, it makes the business case for mercury thrusters virtually unviable. As for Apollo Fusion, the company has stuck to working in the world of ion propulsion, though may have given up mercury propellants at this time. The company, which was acquired by American space launch company Astra, has since flown a xenon thruster in space as part of SpaceX's Transporter-2 mission last year.

In any case, it seems that the thousands of satellites to be put in orbit in coming years will go up to space without mercury-spewing thrusters onboard. That should come as a great relief to all of us down here on Earth, where there is already more than enough mercury pollution as it is.

#currentevents #featured #originalart #science #space #halleffect #halleffectthruster #ionpropulsion #ionthruster #mercurythruster #satellite #spacevehicle #spacecraft