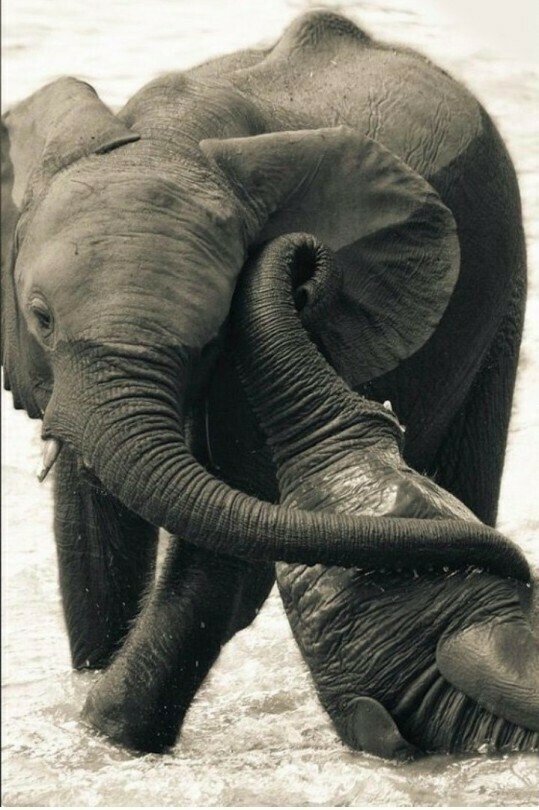

Human-wildlife conflicts are a challenge for authorities in African countries where people live near protected areas. Programmes for communities to participate in wildlife tourism and share its benefits have been put forward as one solution.

Those benefits are substantial in Tanzania. Wildlife tourism is a major source of foreign revenue for the country. In 2021, the tourism sector generated US$2.6 billion, or 5.7% of gross domestic product (GDP).

The country’s 2022 Wildlife Conservation Act offers financial and material compensation for any eligible person negatively affected by human-wildlife conflict incidents. Between 2012 and 2019, more than 1,000 human-wildlife mortality cases were reported nationwide, with rural residents forming the large majority of the victims.

As a sustainability scholar with a research interest in farming and the environment, I set out to understand the experiences of people who’d been victims of human-wildlife conflict in Tanzania. In my study, I spoke with people in the villages of Kiduhi and Mbamba. These two villages share borders with the Mikumi National Park, the fourth-biggest national park in Tanzania.

I asked them about what drives human-wildlife conflict, in their view, when and how they experienced it, how it affected their livelihood or well-being, and what could be done to prevent it in the future.

Incidents of human-wildlife conflict had become common in the two villages, but I found that the victims’ experiences were underreported. I also found that the conflict was driven by habitat losses that pushed wild animals from the park to seek food and water outside. Changing weather patterns also played a role in tensions between wild animals from the park and residents of Kiduhi and Mbamba. Other research has linked changing patterns like this to climate change.

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/EBQVB2CBIFPHBC3TSOHQBD2DNI.jpg)