human hoards hurting the humus

https://www.climbing.com/news/k2-trash-garbage-waste-sickening/

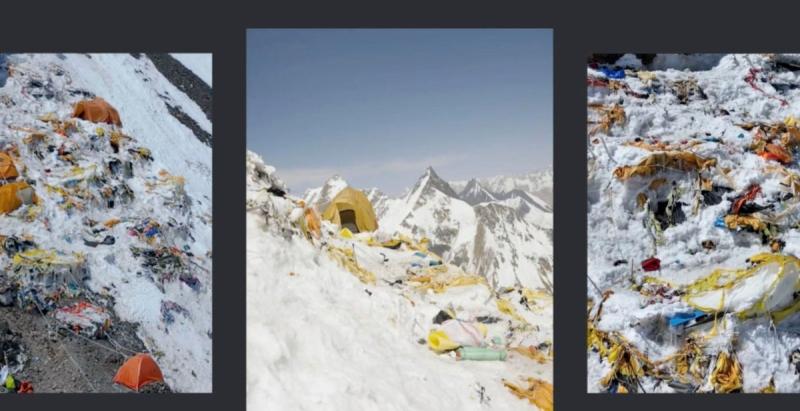

“ #K2, the second-highest peak in the world, has remained relatively free of the commercial circus common on Mount #Everest, but this year the number of climbers ballooned.

Thus far in #2022, some 200 people reached the 28,251-foot summit, including a record-setting 145 people on a single day. Prior to this year, only about 300 people had summited the mountain, ever. This week we saw reports of another Everest-like occurrence on the mountain: heaps of trash.

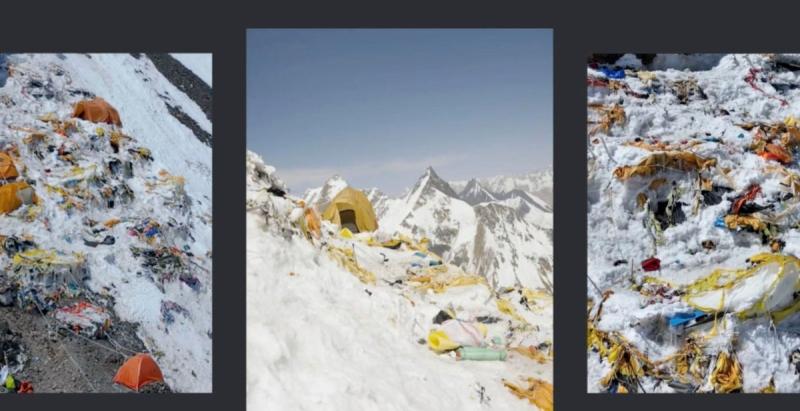

A few days ago Nirmal Purja’s Nimsdai Foundation posted a video of the colorful #carnage at camp two (21,980’). As dramatic strings play in the background, the camera pans across the steep snow slope to reveal dozens of flattened and shredded tents, ropes, pickets, and oxygen canisters. Nirmal Purja, who famously set the speed record for the world’s 14 highest peaks, led a team on the mountain this season and reported that he almost threw up from the #smell. Among the refuse left behind is #human #waste, which doesn’t decompose at altitude and creates serious health risks, since climbers need to melt snow for drinking water.”

“The issue of trash on the world’s highest peaks isn’t new. Everest often gets referred to as the world’s highest landfill, and Outside has reported on the trash (and bodies) piling up every year. But the issue has historically been associated more strongly with Everest, in large part because of the huge crowds. The recent video was particularly jarring because K2 is climbed by far fewer people, because it is more technical and dangerous. Prior to this year, for every four climbers attempting the peak, one would die.

In response to the uproar following his by-then viral trash video, Purja added that the litter shouldn’t necessarily be perceived as malice. “If a climber is ill or struggling, they need to get down the mountains [sic] asap—they may die if they stay to pick up their gear,” he wrote. “Obviously, those climbers that can bring down rubbish, 100 percent should.””

“But that explanation can’t account for the entirety of the problem. Eric Gilbertson, an independent climber who summited without using supplemental oxygen, compared the situation to nearby Broad Peak in a post on an online forum: “I was surprised how much trash was in this camp given that the camps on Broad were generally clean. Both peaks had a similar number of climbers registered for permits and [camp one and camp two] on Broad were also small. The only difference I can think of is K2 has almost exclusively guided groups while Broad had a high percentage of independent groups. Perhaps independent groups clean up after themselves better and don’t leave old tents on the mountain? I’m not sure.”

Gilbertson might be onto something with that analysis. Adrian Ballinger, a professional climber, IFMGA guide, and owner of Alpenglow Expeditions, which leads trips on peaks from Everest to Aconcagua, weighed in: “I think the problem is inexperienced people led by inexperienced high-altitude workers led by inexperienced or unethical expedition leaders.”

In order to offer expedition climbs to clients at a lower price, some operators will opt not to Sherpa or high-altitude workers to pack out trash and gear. “Companies have told me that the reason they don’t bring things like tents down, is they can buy new tents from China that are cheaper than paying Sherpa to go up and do extra rotations and bring their equipment down,” Ballinger says.

Once that trash is on the mountain for a season of melt-freeze cycles, it becomes embedded into the ice and is incredibly difficult to chop out and remove.

As the waste problems have increased, so too have removal efforts. In 2019, cleanup crews hauled some 24,000 pounds of trash off of Mount Everest. Purja is currently raising money to pay for a team of Sherpa to deep clean both Everest and K2 by removing trash and old, dangerous ropes.”

“But while cleanup expeditions are productive, the culture of climbing these peaks has to shift in order to effect meaningful change. Ballinger ran a clean-up on Ama Dablam in 2010, but felt that it actually gave companies permission to do less. “Until we change the culture, a cleanup expedition just encourages poor behavior,” says Ballinger. Two years after the big clean, the trash problem on Ama Dablam was worse than it had ever been before.

Ballinger believes that the movement toward a better mountain experience has to come from the operators, and that clients have to demand it. Many companies, both local and Western operators, pay their support staff to clean up their expedition’s trash. By choosing to climb with these outfitters, prospective clients can support these ethical practices with their wallets.

“If you’re leaving an 8,000-meter peak as a client feeling a little dirty inside about what might have happened on your trip, whether that’s frostbite on your Sherpa or the fact that you left all your poop at camp two—who wants that?” says Ballinger. “None of us are going to be proud of climbing these peaks anymore.””