This one popped up on my Reddit feed as a promoted article for some reason. Why Scientific American feels it's a good idea to promote free articles about deciphering ancient texts I don't know, but it feels like some kind of bizarre swindle to expect to be presented with rampant commercialism but get a quite interesting article instead. How strangely disconcerting.

Almost all classical literature has come down to us from medieval monks, choosy in what they resolved to copy. As a result, relatively little “original” writing from antiquity exists, which means classical literature, from our point of view, is a panorama seen through a pinhole. We have seven plays by Aeschylus, but we know the tragedian wrote at least 10 times more than that. The preserved papyri in Herculaneum are our best shot at rescuing lost works, and some classicists suspect that even more texts could remain in areas of the villa yet to be excavated. “Who knows what’s there?” says Annalisa Marzano, a professor of classical archaeology at the University of Bologna and a trustee of the Friends of Herculaneum Society. In addition to works by the big hitters such as the poets Virgil and Horace, there’s also the tantalizing possibility of finding writing from authors “we know absolutely nothing about,” Marzano says.

Well, I'd certainly like me some more texts from antiquity, who wouldn't ? And, long story short (and it is really quite a long but interesting story), it looks like that's exactly what we're getting.

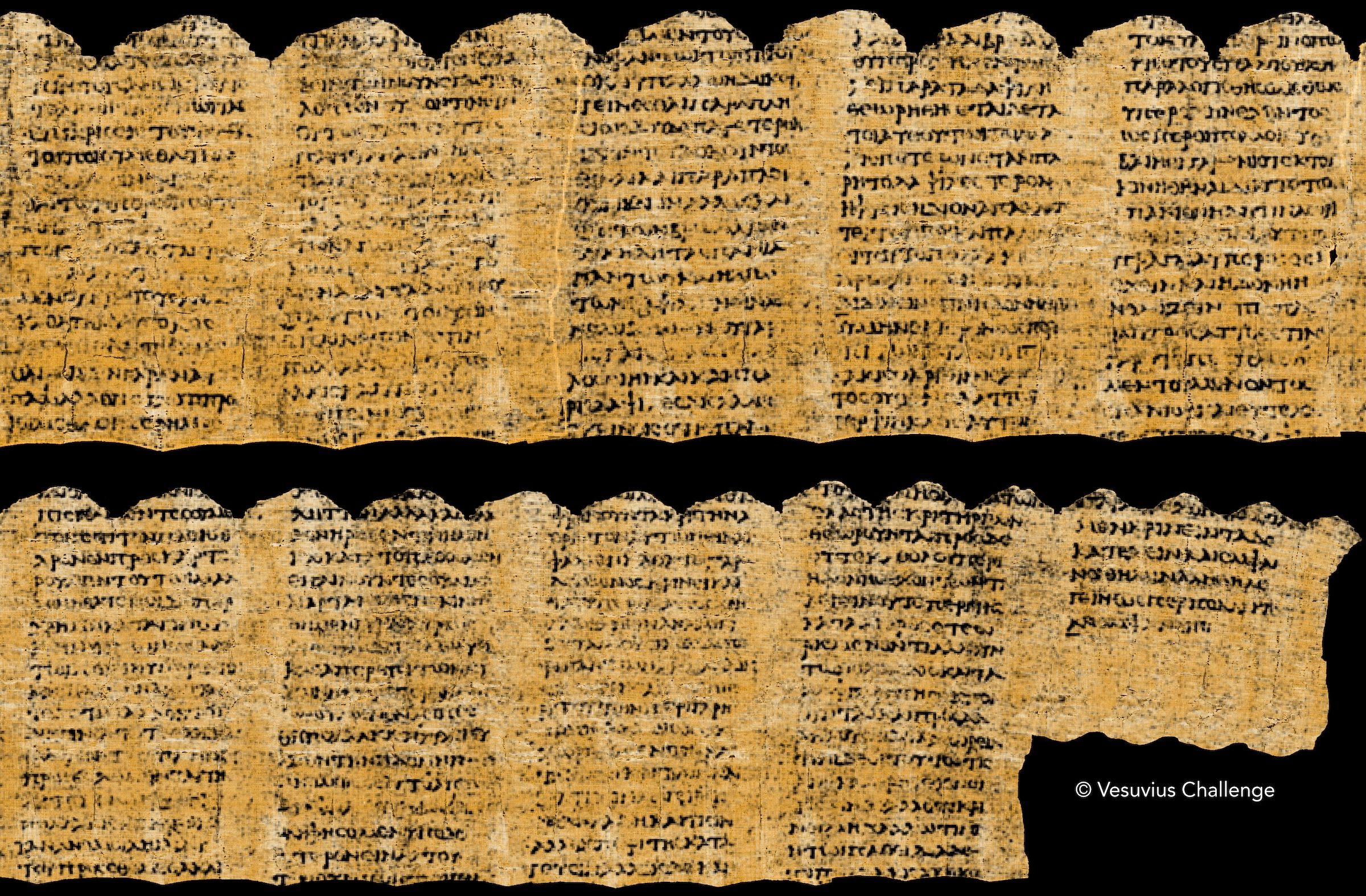

The readable text comprises around 5 percent of the first scroll, and it is from the same text as the earlier discoveries. It is a previously unread tract, probably by Philodemus, about pleasure. Are good things in small quantities more delightful than copious good things? Not at all, the author concludes. “As, too, in the case of food,” writes the author, “we do not right away believe things that are scarce to be absolutely more pleasant than those which are abundant.”

The fields of papyrology and classics are changed forever. Thanks in large part to a group of amateur AI builders, we now have tools for reading the unopened Herculaneum papyri. If the technological advances continue and can be rolled out to the many unopened scrolls, says Tobias Reinhardt, a classics scholar at the University of Oxford who helped to confirm the winning entries, “we could see a recovery of ancient texts at a volume not seen since the Renaissance.”

:extract_focal()/https%3A%2F%2Fcdn.arstechnica.net%2Fwp-content%2Fuploads%2F2022%2F04%2Freally-old-pants-800x450.jpg)