Revealed: richer #graduates in #England will pay less for degree than poorer #students | #Students | The Guardian

The #Tories are even more brazen now in looking after their own. So much for "levelling up".

One person like that

The #Tories are even more brazen now in looking after their own. So much for "levelling up".

Waste bovine bones from the meat industry have been ground into a powder and turned into a collection of light switches and electrical outlets by ÉCAL graduate Souhaïb Ghanmi.

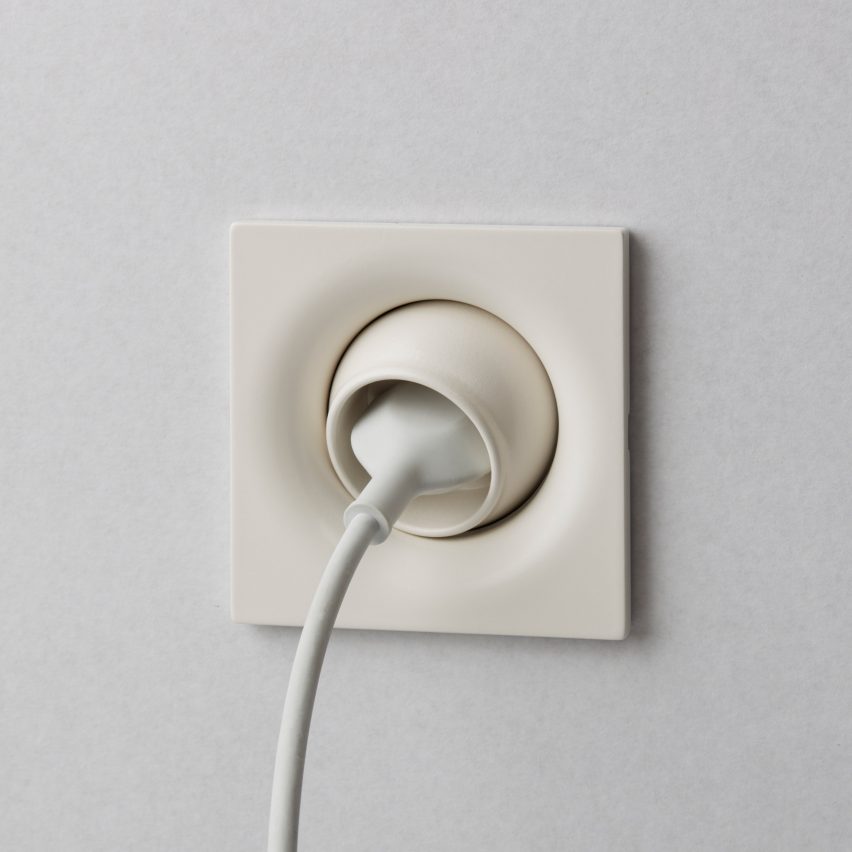

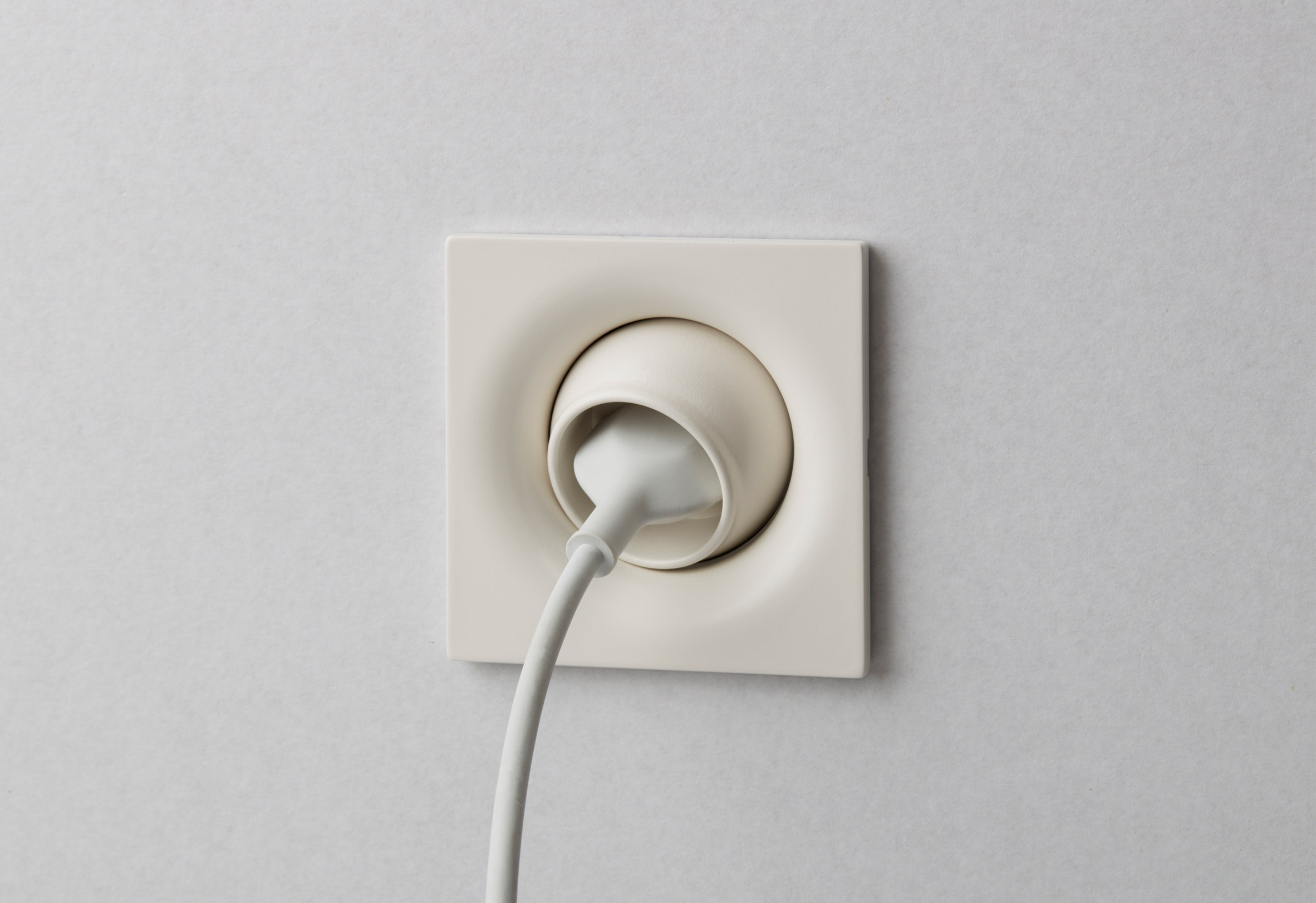

The Elos range features sinuous silhouettes modelled on different parts of the human skeleton, including a socket designed to resemble the head of a thigh bone that is capable of rotating in its baseplate like a hip joint.

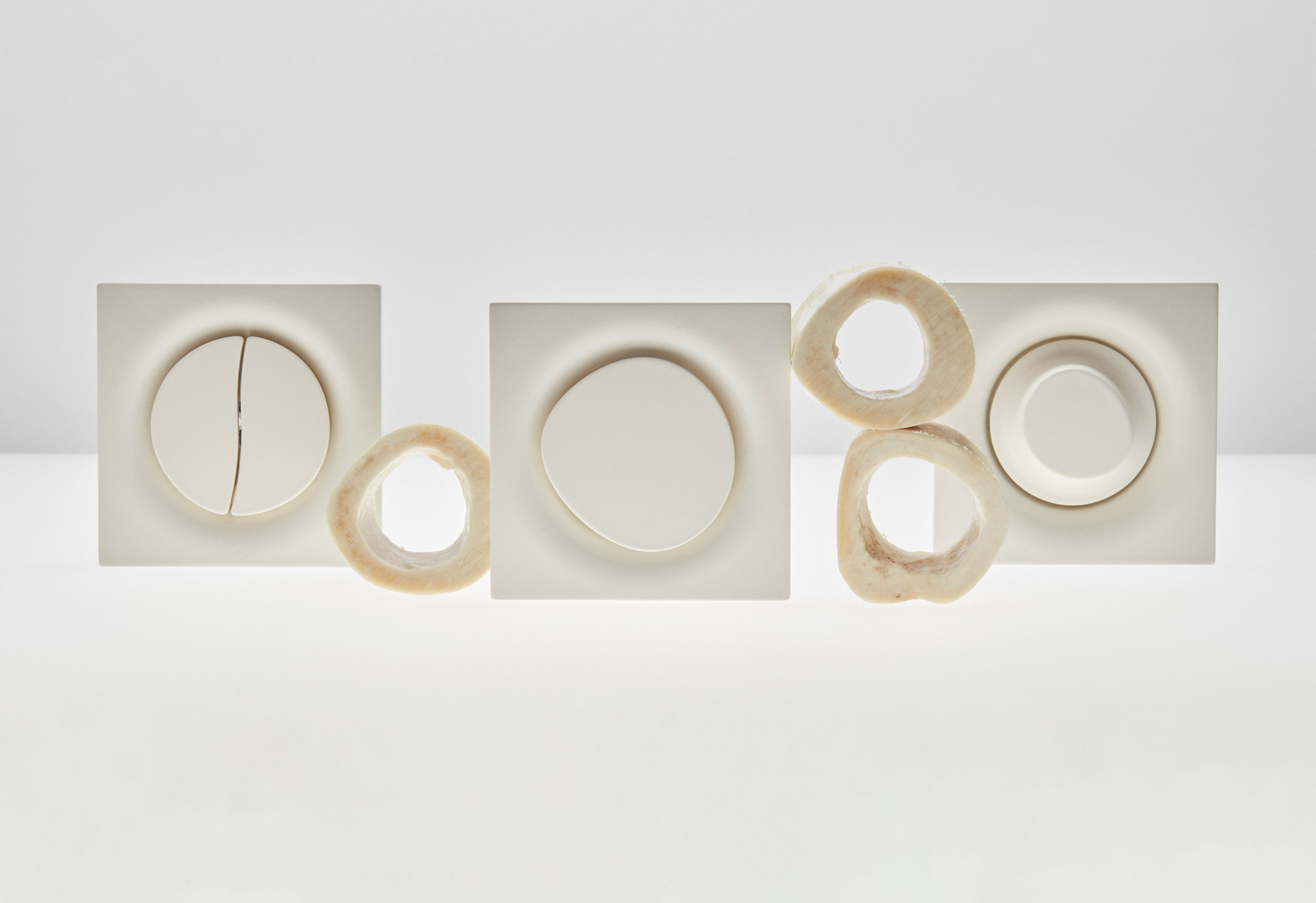

The Elos collection encompasses sockets (above), switches and USB-charging ports (top image)

The Elos collection encompasses sockets (above), switches and USB-charging ports (top image)

Matching light switches and USB charging ports are cast in moulds that reference the organic shape of a cross-sectioned femur but still resemble their conventional plastic counterparts.

By harnessing bone's natural properties as an electric and thermal insulator, the collection finds a renewed purpose for this age-old material, which was traditionally carved into tools or fired to create bone china.

The fittings are made from bone powder mixed with a bio-based binder

The fittings are made from bone powder mixed with a bio-based binder

Ghanmi hopes that his project can help to break our reliance on fossil plastics while making a dent in the more than 130 billion kilograms of bone waste produced by slaughterhouses every year.

"This mineral material, which has no commercial value today, has been used for the manufacture of domestic objects by various peoples throughout history," he told Dezeen.

"In the past, bone was the equivalent of plastic, and nowadays plastic is one of the biggest ecological problems. It is therefore obvious to me to return to this primitive material to apply it to our daily lives."

Phones can rest on the protruding baseplate of the USB port while charging

Phones can rest on the protruding baseplate of the USB port while charging

Ghanmi came up with the idea for the collection after staying with his father's family in rural Tunisia during the Muslim festival of Eid al-Adha, when a ritual animal is sacrificed and its meat split equally between family, friends and those in need.

The festivities allowed Ghanmi to witness first-hand the vast amount of biological waste – such as hooves, hides and tendons – that is generated in the process of slaughtering an animal.

"My uncle used to recover the bones after the festivities and make knife handles out of them," Ghanmi remembered. "Thanks to him, I became curious about this material, which before I considered as waste."

The sockets can rotate to protect cables from wear and tear

The sockets can rotate to protect cables from wear and tear

In Canada and the US – one of the most meat-fed countries in the world – farms and slaughterhouses generate more than 31 million tons of inedible animal by-products every year.

A large part of this ends up in landfills or incinerated, releasing greenhouse gases during decomposition or combustion.

Just over half, around 16 million tons, is processed into useful products by rendering companies. Here, the bones are cleaned, dried and crushed to make fuel, fertiliser, animal feed and gelatin.

[

](https://www.dezeen.com/2021/01/27/valdis-steinarsdottir-food-packaging-vessels-animal-skin-bones/)

Ghanmi sourced the bone powder for his Elos collection from one of these rendering plants and mixed it with a bio-based binder.

As part of his research, the designer experimented with multiple different binder options, including bioresins and different glues made using bovine nerves and bone collagen.

"As I'm currently working on it for a possible development, I'm afraid I can't share specific details of the production," he said. "However, the aim is for the material to only use bones itself and for it to be durable and recyclable."

The light switches are modelled on the shape of a cross-section thigh bone

The light switches are modelled on the shape of a cross-section thigh bone

After being mixed with a binder, the material is cast into the desired shape in a process not dissimilar from the one used traditionally to create switches and sockets, which are compression-moulded using urea-formaldehyde (UF).

This thermosetting plastic does not remelt when exposed to heat, making it suited to use in electronics but at the same time exceedingly difficult and uneconomical to recycle.

In a bid to offer a circular alternative to this, Ghanmi is working on optimising the durability and recyclability of his bone composite so that it can be crushed back into a powder and formed into new products.

The protruding baseplate can also act as a cable reel

The protruding baseplate can also act as a cable reel

Certified for safety and performance, he says bone could be used to substitute plastic components in lighting and electronics, which would help to drive up the demand for animal by-products and create an increased financial incentive for keeping them out of landfills.

Alongside switching to regenerative agricultural practices and reducing meat production overall, this could ultimately help to create a more responsible way of farming livestock.

With a similar aim, Icelandic designer Valdís Steinarsdóttir has previously created vessels from animal bones and collagen that dissolve in hot water, while ceramicist Gregg Moore created tableware for a nose-to-tail restaurant in New York using waste bones from its kitchen.

The photography is byNoé Cotter.

The post Souhaïb Ghanmi uses animal bones instead of plastic for minimalist sockets and light switches appeared first on Dezeen.

#all #products #design #materials #technology #highlights #bones #écal #studentprojects #plugs #graduates

Design Academy Eindhoven graduate Stella van Beers has created a watchtower-style house inside a grain silo.

In a project called Silo Living, Van Beers transformed the disused agricultural structure into a two-level living space, which she believes could function as a short-term home.

The project converts a seven-metre-high grain silo

The project converts a seven-metre-high grain silo

While silos are not ideally proportioned for living, they offer some unique benefits. They can often be installed in rural locations without planning permission.

They are also readily available in the Netherlands as a country-wide reduction in livestock has resulted in lower demand for grain, leaving many of these structures redundant.

The designer had to add doors, windows and floors

The designer had to add doors, windows and floors

Van Beers hopes to inspire new uses for these disused silos, which are otherwise costly to dispose of and impossible to recycle.

"You always see them in rural areas," she told Dezeen. "I always really wanted to go inside one, so thought it could be a nice place for a temporary stay."

Van Beers created two storeys inside the silo

Van Beers created two storeys inside the silo

To test her concept, the designer found a seven-metre-high silo for sale online. "I thought, if I want to do something with a silo then I have to just buy one and see what's possible," she said.

After explaining her plans to the owner, he let her take it away for free.

A spiral staircase and deck provides access

A spiral staircase and deck provides access

Originally there was no way for a person to enter the silo, so Van Beers started by changing that.

She installed a set of double doors, then added a spiral staircase and access deck.

[

To make the most of the space inside, she installed two floors, connected by a mini staircase and ladder.

The lower level is a living space, with a ledge that functions as a space to eat or work.

A mini staircase and ladder connects the levels inside

A mini staircase and ladder connects the levels inside

The mezzanine above is a sleep space, so is entirely taken up by a mattress.

Both storeys now have projecting windows and there's also a skylight that functions as a lookout point.

Windows were added to both floors

Windows were added to both floors

"A cylindrical house is not something you see very often, so it was a bit of a challenge," said Van Beers.

Most of the adaptations use standard components, so could be easily replicated on a variety of silos. The designer hopes to inspire silo owners to get creative.

The windows project out, creating some additional space

The windows project out, creating some additional space

"There are a lot of things I would change if I made another," she said, "but I'm really happy with this as a first prototype. A few people have slept in it already."

"If you have a bigger silo, you could use it as a living space for a longe amount of time," she suggested.

A porthole in the top creates a lookout point.

A porthole in the top creates a lookout point.

Van Beers created the project for her bachelors degree at Design Academy Eindhoven. She presented it at the graduation show, which took place during Dutch Design Week in October.

Other projects on show included glass blown inside bread and "trauma-healing" garments.

The post Stella van Beers converts grain silo into micro home appeared first on Dezeen.

#residential #all #architecture #videos #netherlands #designacademyeindhoven #studentprojects #architecturevideos #microhomes #residentialconversions #graduates

Design graduate Kukbong Kim has developed a paint made from demolished concrete that is capable of absorbing 20 per cent of its weight in carbon.

Called Celour, the paint can sequester 27 grams of CO2 for every 135 grams of paint used.

"That is the same amount of carbon dioxide that a normal tree absorbs per day," Kim said.

The indoor-outdoor paint is made of waste concrete powder, a cement-based residue from concrete recycling that is normally buried in landfills, where it can alkalise the soil and have a detrimental effect on local ecosystems.

Celour is a carbon-capturing paint that comes in three colours

Celour is a carbon-capturing paint that comes in three colours

Through a chemical process called mineral carbonation, which takes place when the paint reacts with the CO2 in the surrounding air, Kim says Celour can reabsorb a significant part of the emissions that were generated by producing the cement in the first place.

Eventually, she hopes to optimise the capturing capacity of the paint so that it completely negates the carbon footprint of the cement it is made from.

"I think it is too early to describe Celour as carbon neutral," Kim said. "It needs further study but I want to make it a carbon-negative product. That is my goal."

"It's not enough if we just stop emissions, as we already have high levels of CO2 in the air," she added. "We need to participate in CO2 removal in our daily lives."

Concrete naturally reabsorbs some of the carbon it emits

Cement is the most carbon-intensive ingredient in concrete and is responsible for eight per cent of global emissions.

But when concrete is recycled, only the aggregate is reused while the cement binder is pulverised to create waste concrete powder and sent to landfill, where it can disturb the pH balance of the surrounding soil.

"Waste concrete powder is high in calcium oxide," Kim explained. "And when it is buried and comes into contact with groundwater or water in the soil, it turns into calcium hydroxide, which is strongly alkaline."

The waste concrete powder is filtered, pulverised and mixed with a binder, water and pigments

The waste concrete powder is filtered, pulverised and mixed with a binder, water and pigments

With her graduate project from the Royal College of Art and Imperial College London, the designer hopes to show the usefulness of this industrial waste material by maximising its natural ability to capture carbon.

Studies have shown that cement already reabsorbs around 43 per cent of the CO2 that is generated in its production through the mineral carbonation process.

This is set off when concrete is cured by adding water, which reacts with the calcium oxide in the cement and the CO2 in the air to form a stable mineral called calcium carbonate or limestone.

A traditional concrete block continues to cure throughout its life but because this process is reliant on exposure to air, only its outer layers will react with the CO2 while its core will remain uncarbonated.

Celour could store carbon for thousands of years

But Kim was able to improve the material's carbon-capturing capabilities by turning the waste concrete pounder into a paint, mixed with a binder, water and pigments.

This is spread thinly on a surface so that more of the material is exposed to the air and can carbonate.

In addition, the coarse powder was further filtered and pulverised to increase the relative surface area of the particles while a polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) binder creates small gaps for air to enter.

"I have done a lot of experiments with different ingredients to maximise carbon absorption by increasing the surface area that comes into contact with carbon dioxide in the air," she explained.

"Graphene, which can capture lots of carbon thanks to its structure, was also considered as a binder but excluded because it is currently priced high and cannot be mass-produced."

The paint can be used both indoors and outdoors

The paint can be used both indoors and outdoors

Cement has long been used to create traditional paint, which is also capable of sequestering CO2. But Kim hopes to harness these carbon-capturing benefits while keeping a polluting waste material out of landfills and avoiding the emissions associated with making new cement.

How long the paint is capable of storing carbon is dependent on what happens to it after it is no longer needed. But Kim says it could be locked away for thousands of years unless exposed to extreme heat, which would alter the chemical structure of the carbonate.

As part of our carbon revolution series, Dezeen has profiled a number of carbon capture and utilisation companies that are working on turning captured CO2 into useful products from bioplastic cladding to protein powder and concrete masonry units.

The post Carbon-capturing Celour paint allows anyone to "participate in CO2 removal in their daily lives" appeared first on Dezeen.

#all #products #design #royalcollegeofart #productdesign #concrete #studentprojects #materials #graduates #paint #cement #carboncapture #carboncaptureandutilisation #mineralcarbonation

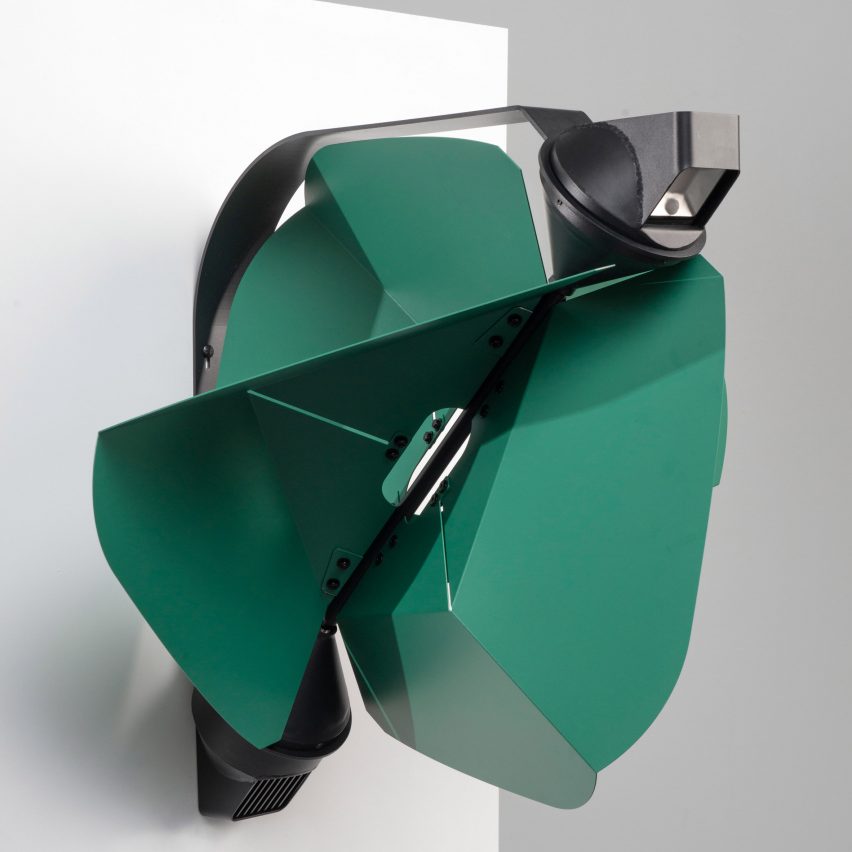

Berlin design student Tobias Trübenbacher has developed a lamp post with an integrated wind turbine that produces its own renewable energy and only lights up when needed.

Papilio was designed to slash the light pollution and emissions associated with street lighting and mitigate its impact on both humans and animals as well as the environment.

The motion-activated design uses wind – a natural, renewable energy source – to power its turbines.

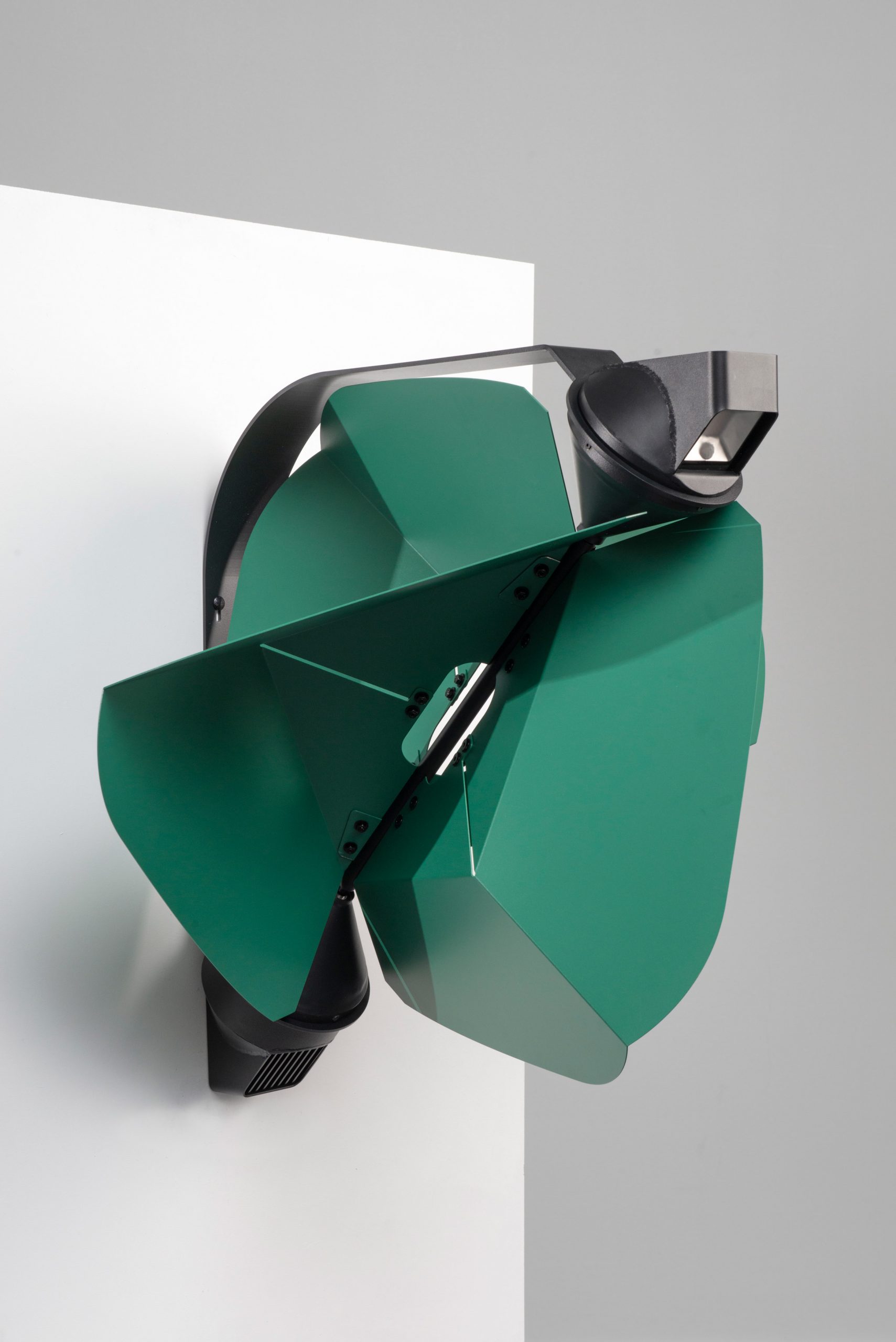

Above and top image: the Papilio light can be wall-mounted or freestanding

Above and top image: the Papilio light can be wall-mounted or freestanding

"If we want to maintain a future worth living in, we urgently need to transform our cities into climate-neutral, sustainable and less harmful places," Trübenbacher told Dezeen.

"We urgently need to tackle light pollution and the loss of biodiversity coming along with it. This can only happen if cities generate energy themselves – through locally embedded, decentralised systems and 'prosumer' products in huge quantities spread all over urban spaces. In this context, wind represents an often underestimated yet constantly growing potential."

Its matt black body is designed to reflect as little light as possible

Its matt black body is designed to reflect as little light as possible

Papilio can be mounted to walls or set up as a freestanding lantern. The lamp should ideally be placed between three to six metres above ground, where ground-level winds are the strongest.

These winds are harnessed by a turquoise, pinwheel-shaped wind turbine with four aerodynamic rotor blades made of folded sheet metal.

The turquoise wind turbine is propelled by urban airstreams

The turquoise wind turbine is propelled by urban airstreams

Angled diagonally, the rotor can reportedly make use of complex airflows in urban environments including natural currents, wind tunnels created by tall buildings and smaller airstreams caused by passing vehicles.

The turbine then converts the wind's kinetic energy into mechanical power, before an integrated 300-watt generator turns it into electricity and stores it in a rechargeable battery.

Its shape resembles a pinwheel

Its shape resembles a pinwheel

"I have already tested the lights at several locations in Berlin and under normal wind conditions, the generator generated an average of up to 12 volts of electricity at any given time," Trübenbacher explained.

"Since today's LED technology is becoming more and more efficient, this amount of energy is easily enough to charge the integrated battery and operate bright light."

Applied at scale, he says the light could help to illuminate our cities without generating carbon emissions along the way.

"The world's population continues to spend nearly a fifth of the total global electricity consumption on public lighting and thereby releases a significant amount of greenhouse gases," Trübenbacher said.

"In Germany alone, street lightning emits at the moment around 2.5 million tons of CO2 per year."

Each turbine has four rotor blades made of folded sheet metal

Each turbine has four rotor blades made of folded sheet metal

Papilio is completely self-sufficient and could operate without the need for an "expensive underground electricity infrastructure", Trübenbacher explained.

Alternatively, the lights could be hooked up to the local power grid and divert any surplus energy to the city.

The light is a full cutoff fixture, meaning its head is pointed directly downward to minimise light pollution

The light is a full cutoff fixture, meaning its head is pointed directly downward to minimise light pollution

To mitigate the effects of light pollution on both people and animals, Papilio is equipped with an infrared motion sensor that only switches on the light when someone is passing by.

Its head is a so-called full cutoff fixture, meaning it is angled straight down towards the floor and does not emit any light upwards, while the light itself has an extra-warm, insect-friendly colour temperature of 2,800 Kelvin.

Trübenbacher tested the light in various locations in Berlin

Trübenbacher tested the light in various locations in Berlin

Trübenbacher fine-tuned the light spectrum in collaboration with a group of scientists and researchers to be less appealing to insects, whose attraction to conventional blue-toned street lights makes them vulnerable to predators as well as collisions, overheating and dehydration.

"Light pollution not only has bad health effects on humans – like causing sleep disorders, depression, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and cancer – but has also a serious impact on flora and fauna," Trübenbacher explained.

"It is estimated that currently in Germany alone, in one single summer night around 1.2 billion insects die because of street lighting."

It can be assembled from simple components

It can be assembled from simple components

In a bid to illuminate our cities in a more sustainable way, other designers have instead drawn on the energy of the sun to create self-sufficient street lights.

Mathieu Lehanneur created petal-shaped outdoor lamps with integrated photovoltaic panels and spindly wooden stems for the 2015 Paris Climate Conference, while Ross Lovegrove worked with Artemide to set up his Solar Tree in cities around the world.

The post Papilio is a wind-powered street lamp that reduces light pollution appeared first on Dezeen.

#all #lighting #design #technology #sustainabledesign #studentprojects #streetlighting #graduates #windturbines #renewableenergy

Harvard Medical School Graduates

I say good night!

off wid diz great #quote by #Harvard #graduates,

"They Tried to Bury Us,They Did'nt Know We Were Deeds."