Are you looking for new landscapes away from the crowds and the tripod holes of the national parks? Are you seeking a more adventurous and out-of-the-beaten-path experience? If so, how about a visit to America's national monuments?

The term "national monument" may remind photographers of Lee Friedlander's influential but quirky book The American Monument, which featured a collection of memorials and statues all over the country. So what's in there for a landscape photographer?

In the United States, the term has a more specific meaning and, at the same time, includes features more general than built landmarks. Defined by a 1906 law called the Antiquities Act, national monuments are federally protected areas containing objects of historic or scientific interest. The main difference with national parks is administrative. The President can swiftly proclaim national monuments with only a signature, thus providing expedited protections, whereas only Congress can establish national parks.

As suggested by its name, the Antiquities Act was initially meant to protect native archeological sites. However, the first national monument was Devil's Tower in Wyoming, a natural feature of geologic interest. Congress had been debating over the Grand Canyon since 1882, but even as commercialism was running unchecked, by 1908, it had not yet acted to protect that quintessential American wonder. President Theodore Roosevelt did, by proclaiming the Grand Canyon a national monument.

Since 1906, 16 presidents have used the Act to preserve some of America's most treasured public lands and waters. Half of today's national parks were first protected as national monuments.

While some national monuments fit within an acre, others protect entire landscapes with natural features as extraordinary as those found in national parks. In some sense, those landscape-scale national monuments could be seen as national parks in waiting. An excellent example is Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument located in Southern Utah. At 1,880,461 acres, it is significantly larger than Grand Canyon National Park (1,217,403 acres).

Within its plateaus descending in vividly colored stair-steps from Bryce Canyon to the Grand Canyon, the monument protects significant paleontological sites. However, for the visitor, the attraction is its extraordinary geology of cliffs, badlands, hoodoos, natural arches, and canyons.

Moonrise over Cockscomb from Yellow Rock. Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument, Utah, USA

Moonrise over Cockscomb from Yellow Rock. Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument, Utah, USA  Sunset Arch, dawn. Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument, Utah, USA

Sunset Arch, dawn. Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument, Utah, USA  Swirls and hoodoos, Devils Garden. Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument, Utah, USA

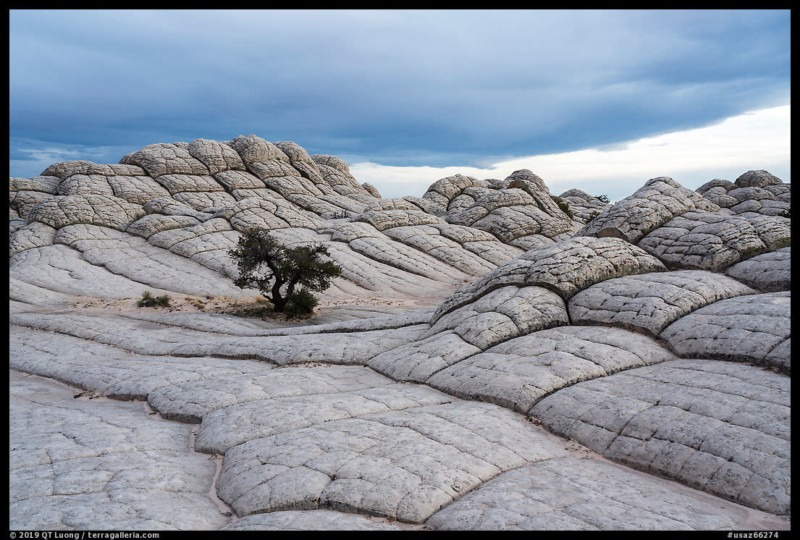

Swirls and hoodoos, Devils Garden. Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument, Utah, USA  Zebra Slot Canyon with sandstone striations and encrusted moqui marbles,. Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument, Utah, USA

Zebra Slot Canyon with sandstone striations and encrusted moqui marbles,. Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument, Utah, USA

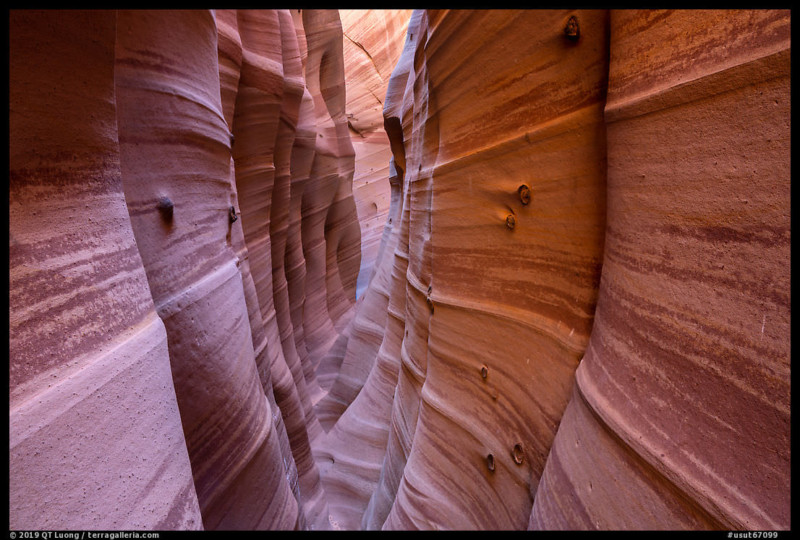

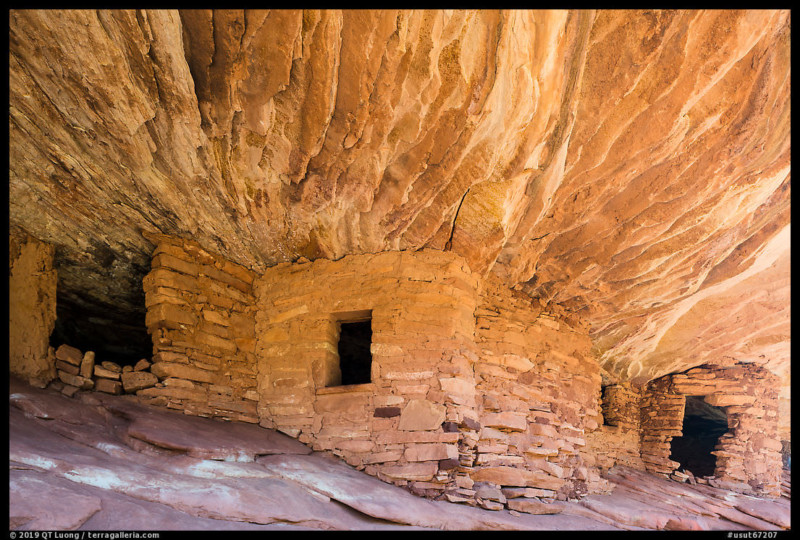

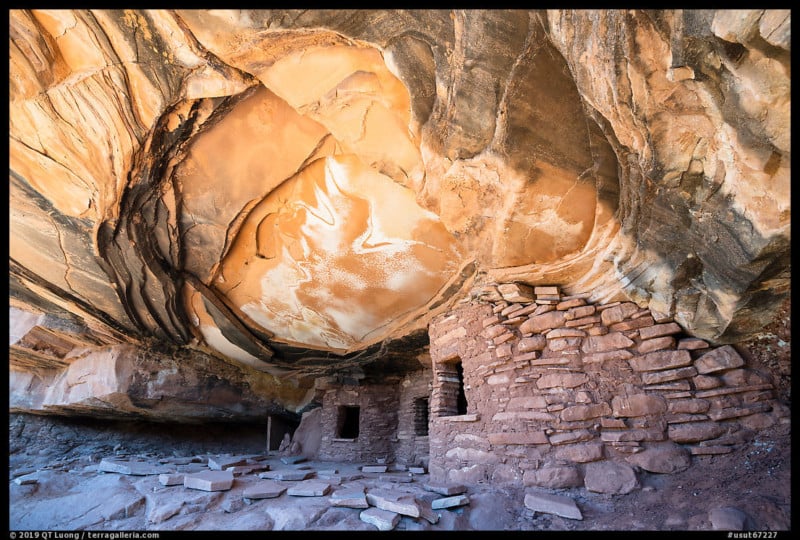

Nearby Bears Ears National Monument shares many characteristics with Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument: its location in Southern Utah, its size (1,353,000 acres) larger than Grand Canyon National Park, and wondrous red rock country with even more immense vistas. However, it is primarily a cultural landscape. Hidden in its labyrinth of canyons and mesas are more cliff dwellings and tribal artifacts than any other area in the American West, including some of the most iconic ruins on the Colorado Plateau.

Both monuments marked milestones in conservation. Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument, proclaimed in 1996 by President Clinton, was the first national monument managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), marking the evolution of the nation's largest land caretaker towards conservation. The Hopi, Navajo, Mountain Ute, Zuni, and Ute agreed to set generations-old differences apart to petition for the protection of their ancestral lands.

In response, in the waning days of his presidency, President Obama proclaimed Bear Ears National Monument in 1996, the first national monument initiated by native people and co-managed by them.

Valley of the Gods from above. Bears Ears National Monument, Utah, USA

Valley of the Gods from above. Bears Ears National Monument, Utah, USA  Flame Ceiling Ruin, Mule Canyon. Bears Ears National Monument, Utah, USA

Flame Ceiling Ruin, Mule Canyon. Bears Ears National Monument, Utah, USA  Ruin in alcove with collapsed ceiling. Bears Ears National Monument, Utah, USA

Ruin in alcove with collapsed ceiling. Bears Ears National Monument, Utah, USA  Light from Perfect Kiva and moon. Bears Ears National Monument, Utah, USA

Light from Perfect Kiva and moon. Bears Ears National Monument, Utah, USA

National monuments are much less known and visited than national parks, but those two just have been in the news since 2017. In the spring of that year, President Trump signed an unprecedented executive order to review all the national monuments created through the Antiquities Act since 1996 that were larger than 100,000 acres. The review's objective was to determine if former presidents had abused their power and if the protections curtailed economic growth.

It targeted a total of 27 out of the 35 larger national monuments, including 22 national monuments across 11 states, in addition to five even larger marine areas. The public comment period of the summer of 2017 generated 97% support for the national monuments under review. Yet, on December 4, 2017, the President ordered size reductions to the two national monuments located in Utah mentioned above.

In January 2018, I resolved to take action the only way I knew, by hiking and photographing the 22 land-based national monuments in the review. I found a broad cross-section of natural environments, covering a significant portion of the American landscape. Totaling about 11 million acres, they ranged from the north woods of Maine to the cactus-covered deserts of Arizona.

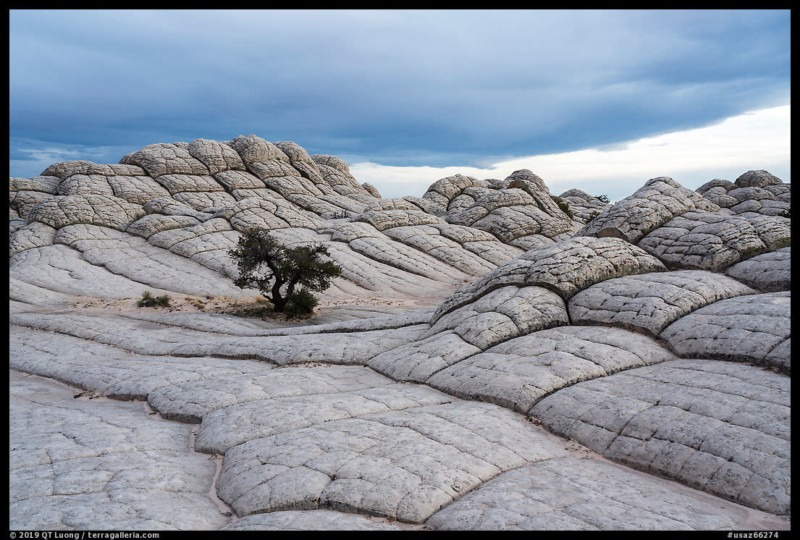

Besides their vastness and diversity, their natural features rivaled those in our beloved national parks. Vermilion Cliffs National Monument's Paria Canyon is more than twice as long and every bit as impressive as Zion National Park's Virgin River Narrows. The monument also houses unique world-renowned rock formations like The Wave and the White Pocket.

Giant Sequoia National Monument protects more sequoia groves than Sequoia and Kings National Parks. The Sonoran Desert portions included in Ironwood Forest National Monument and Sonoran Desert National Monument are as beautiful and representative as those in Saguaro National Park, if not more pristine.

I spent months in repeated visits, immersing myself in those sacred lands and discovering remnants of cultures imprinted on the ancient landscape. So many of those monuments were previously unknown to me. I reasoned that those areas were vulnerable because the general public did not know about them and thus was not moved to defend them. This inspired me to publish a book that could help conservation organizations raise awareness of those lands.

To amplify the call for conservation, I invited those who advocate for these national monuments to present their perspective. I am so grateful to 27 local citizen associations caring for those national treasures for contributing their voices, to former Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell for her foreword, and to Ian Shive for his photographs and words that give readers a glimpse of the almost inaccessible marine national monuments in the Pacific.

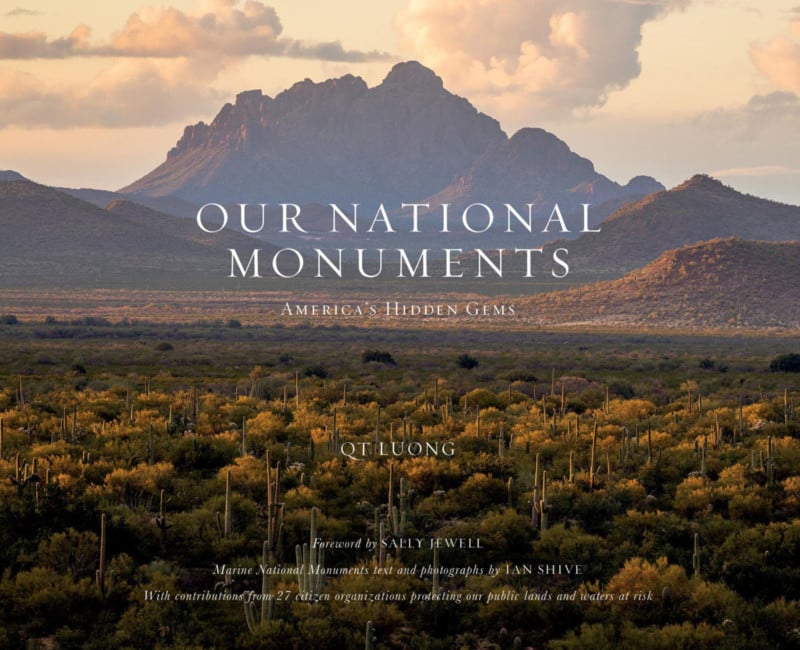

The result is the first photography book entirely dedicated to America's national monuments. While it includes only a subset of them (the 27 monuments at risk from the review), those comprise the vast majority of the large, park-like monuments. Our National Monuments: America 's Hidden Gems is the first in-depth portrayal of those parks less traveled.

After spending a big part of the previous quarter-century photographing the national parks, I was surprised by the freedom offered by the BLM and the U.S. Forest Service's (USFS) national monuments. Freedom from crowds, from rules, and expectations.

The national parks, set for "benefit and enjoyment of the people," are generally equipped with a convenient infrastructure of roads, visitor centers, lodges, campgrounds, and interpretive trails. Set up for mass tourism, they can bring in mass visitation. For example, this year Arches National Park was frequently full and closed to new entries by 9 am. People instead head to nearby Canyonlands National Park, but even there, securing a spot at sunrise for the iconic Mesa Arch requires arriving well in advance.

Next year, you will need a reservation to enter Arches National Park. By contrast, when I photographed three of the better-known natural arches in nearby Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument, I had the entire place to myself. Despite a dozen visits to Death Valley National Park, I could never find the Mesquite Sand Dunes devoid of numerous footprints from other visitors. At Cadiz Dunes Wilderness in Mojave Trails, I saw many animal tracks but no human footprints, aside from my own.

During the worst days of the pandemic, national parks locked their gates. Embodying the principle that public lands are always open to the public, national monuments never closed, providing much solitude and solace. The heavy visitation of national parks made it necessary to enforce strict rules. You often have to "commute" a long distance to photography spots as no car camping is allowed outside developed campgrounds.

In many national monuments, you can camp almost everywhere you like. Unlike in Grand Canyon National Park, in adjacent Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument, I could drive right to the edge of the chasm and pitch my tent a few yards away from where I made my sunset, night, and sunrise photographs. Drones are strictly prohibited in national parks, but they are allowed in the national monuments managed by the BLM and the USFS.

Many national parks places have become such over-photographed icons that finding a fresh composition has become as challenging as securing a spot. The national monuments offer new landscapes whose more subtle scenery invites exploration to get to know and love. The absence of postcard views and overwhelming features frees you of pre-conceptions that hinder personal discovery.

Succulents on Grand Canyon Rim at dusk. Parashant National Monument, Arizona, USA

Succulents on Grand Canyon Rim at dusk. Parashant National Monument, Arizona, USA

As the national parks become ever more popular, the BLM and USFS national monuments' vast open spaces offer us places of solitude and inspiration. The rugged experience gives us a sense of the western frontier. With freedom comes the need for personal responsibility, independence, and self-reliance.

As their development is minimal, national monuments can test your preparation and self-sufficiency. Many do not have a single paved road. I needed to rent a 4WD vehicle several times to access some of them. Even then, I still ended up with five flat tires over three years, sometimes in incredibly remote areas. With no visitor centers nor rangers around, no brochures, nor guidebooks, the first obstacle in my explorations was to find information.

Our National Monuments: America 's Hidden Gems provides you with the starting point I wish I had for planning trips. Coffee-table books about places often left me frustrated about being in the dark about the locations depicted. With my previous book, Treasured Lands: A Photographic Odyssey Through America's National Parks, I had aimed to create a book that inspired and informed. Each photograph came with extended practical travel and photography notes, including facts on the parks' natural history or anecdotal observations about my experiences.

Although people in the publishing industry were skeptical that this combination of an artbook and guidebook would work, the book won twelve national and international awards and is also a best-seller in its sixth printing.

My new book, Our National Monuments , reprises this innovative format, depicting each national monument in depth through a selection of representative highlights with keyed maps and location information. Because those lands are not as popular as the national parks, I do not expect the new book to be as commercially successful. But, on the other hand, the general lack of awareness of those lands is also why I felt this book is needed, a sentiment echoed by the grassroots conservation organizations that care for those critical landscapes.

Our National Monuments is my gift to our public lands and those who care for them.

On October 8, 2021, President Biden finally restored the two national monuments in Utah – and one in the Atlantic Ocean. Was it all a bad dream? Republican politicians in Utah are gearing up for a lawsuit to challenge the restoration. The 2017 presidential attack on them reminded us of John Muir's appeal that "the battle for conservation will go on endlessly."

It reminded us that since 1906, America's boldest efforts in conservation have been through the proclamation of national monuments. It prompted me to set out to see for myself the magnificent landscapes of the parks less traveled. I hope it prompts you to learn about our public lands' hidden gems and embark on your own journey.

_Our National Monuments: America 's Hidden Gems by QT Luong features over 330 photographs of 27 national monuments by 36 contributors. The 10×12-inch 308-page hardcover photo book also contains 28 maps and over 70,000 words. It's available from Amazon and other retailers for $55._

About the author : QT Luong was the first to photograph all America's 62 National Parks -- in large format. The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. Luong was featured in the film _The National Parks: Americaʼs Best Idea by Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan. His photographs are extensively published and have been the subject of large-format books including Treasured Lands (winner of 10 national and international book awards), many newspaper and magazine feature articles, solo gallery and museum exhibits across the U.S. and abroad. You can find more of his work on his website, Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook._

#educational #inspiration #spotlight #travel #america #landscape #landscapephotography #nationalmonuments #qtluong #unitedstatesofamerica