Just read this in this years O Henry Awards...blown away

https://harpers.org/archive/2023/06/seeing-through-maps-madeline-ffitch/

4 Likes

Just read this in this years O Henry Awards...blown away

https://harpers.org/archive/2023/06/seeing-through-maps-madeline-ffitch/

In Case of Complete Reversal

By Kay Ryan

Born into each seed

is a small anti-seed

useful in case of some

complete reversal:

a tiny but powerful

kit for adapting it

to the unimaginable.

If we could crack the

fineness of the shell

we’d see the

bundled minuses

stacked as in a safe,

ready for use

if things don’t

go well.

I'm reading #DonQuixote by #MiguelDeCervantes at the moment and thoroughly enjoying it. Before overhearing a little of it in an audiobook not long ago, I realized that it was not a dry #book at all. There are glimpses of what later authors, like #PGWodehouse and even #TerryPratchett took from it and also characters like #InspectorClouseau show traits of the deluded hero of the book. I will reserve further judgement until I get to the end but I'm finding it a pleasure rather than a chore right now.

**

From the Writer’s Almanac 11/17/2013**

It’s the birthday of American novelist and historian Shelby Foote, born in Greenville, Mississippi (1916). He was a successful novelist when, in 1952, he accepted the suggestion of his publisher to write a short history of the Civil War to complement his novel Shiloh (1952). Foote is best known for his trilogy, The Civil War: A Narrative.

He grew up on the Mississippi-Yazoo Delta, once a great swamp filled with alligators and water moccasin snakes. As a teenager, Foote sold poems to magazines for 50 cents apiece. He was editor of the high school paper and liked to give the principal a hard time. When Foote applied to attend college at Chapel Hill, the principal wrote a letter saying not to let Foote into their school under any circumstances. Foote got in his car and drove to North Carolina to register anyway and they let him in. He was a literary prodigy there along with his classmate Walker Percy, who was his best friend for 60 years.

When Foote was 19 years old, he and Walker Percy were planning to drive from Foote’s hometown, Greenville, Mississippi, through William Faulkner’s hometown of Oxford, Mississippi. Foote suggested they stop in Oxford and try to meet him. Percy waited in the car while Foote went up the cedar tree-lined walkway to Faulkner’s house. He was greeted in the yard by three hounds, two fox terriers, and a Dalmatian. Soon, a small man, barefoot and wearing just a pair of shorts, appeared and asked Foote what he wanted. “Could you tell me where to find a copy of Marble Faun, Mr. Faulkner?” Foote asked. Faulkner was gruff and told him to contact his agent. Faulkner later befriended Foote, who walked Faulkner around the Civil War battlefields of Shiloh.

Foote once told Faulkner on one of their outings: “You know, I have every right to be a better writer than you. Your literary idols were Joseph Conrad and Sherwood Anderson. Mine are Marcel Proust and you. My writers are better than yours.”

Foote spent the last 25 years of his life working on an epic novel about Mississippi called Two Gates to the City. It remained unfinished when he died in 2006.

https://writersalmanac.publicradio.org/index.php%3Fdate=2013%252F11%252F17.html

From the Writer's Almanac 11/15/2013

It's the birthday of American artist Georgia O'Keeffe, born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin (1887). She studied art in college and then supported herself teaching art at various colleges, but she found that teaching left her no time for her own work, and the turpentine smell of the art classrooms made her sick. She went for months and years on end without painting anything, only to start over again and try something new.

On a trip to Taos, New Mexico, O'Keeffe fell in love with the desert. She felt that the thin, dry air helped her to see better, and she devoted the rest of her career to painting desert mountains, flowers, stones, and skulls.

Georgia O'Keeffe said: "Nothing is less real than realism. Details are confusing. It is only by selection, by elimination, by emphasis, that we get at the real meaning of things."

https://writersalmanac.publicradio.org/index.php%3Fdate=2013%252F11%252F15.html

When readers say they prefer AI poetry, then, they would seem to be registering their frustration when faced with writing that does not yield to their attention. If we do not know how to begin with poems, we end up relying on conventional “poetic” signs to make determinations about quality and preference.

This is of course the realm of GPT, which writes formally adequate sonnets in seconds. The large language models used in AI are success-orientated machines that aim to satisfy general taste, and they are effective at doing so. The machines give us the poems we think we want: ones that tell us things.

https://social.seattle.wa.us/@jaimeJ/113477576971602017 jaimeJ@social.seattle.wa.us - "A Moment Of Peace" teableau for 11/13/24

Personally, I take peace in the knowledge of a woman operating within the confines & restrictions of Regency England reaching across the centuries to remind us of how subversive she could be.

#Tea #Teableau #TeaCozy #TeaCosy #BlackTea #Handmade #Sewing #VintageChina #bookstodon #Books #Literature #JaneAusten #Embroidery

Jack Gilbert is one of the best poets I know of!

Alone

by Jack Gilbert

I never thought Michiko would come back

after she died. But if she did, I knew

it would be as a lady in a long white dress.

It is strange that she has returned

as somebody's dalmatian. I meet

the man walking her on a leash

almost every week. He says good morning

and I stoop down to calm her. He said

once that she was never like that with

other people. Sometimes she is tethered

on their lawn when I go by. If nobody

is around, I sit on the grass. When she

finally quiets, she puts her head in my lap

and we watch each other's eyes as I whisper

in her soft ears. She cares nothing about

the mystery. She likes it best when

I touch her head and tell her small

things about my days and our friends.

That makes her happy the way it always did.

Jack Gilbert died on this day in 2012.

Jack Gilbert, "Alone" from Collected Poems. Copyright © 2012 by Jack Gilbert. Reprinted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/58412/alone-56d23cc3c2dbe?mc_cid=e6fcc3424a

CRIBBAGE LESSONS

by Susan Johnson

The summer Dad decided it was time

I learned crib, counting fifteen two,

fifteen four, I loved doing the sums

in my head, tallying up the pairs,

runs, as if life were arithmetic,

which at six it was. Going into

second grade, the owner of three

hand-me-down bathing suits from

one sister, two cousins, I went

swimming five times a day and at

the general store one mile away,

bought a dime’s worth of penny

candy from a woman who had to

be a hundred. In four years mom

would have her mastectomy; in ten

she’d be dead. We didn’t know any

of that then. Just that it all adds up

until it doesn’t. Then you’re skunked.

—from Rattle #85, Fall 2024

Susan Johnson: “I spent my childhood being outside as much as possible and trying to solve the many puzzles that made up my life. I do the same as an adult, only now it’s language that I use to work through and understand what I encounter. I’m also more accepting when it doesn’t quite add up.”

Veterans of the Seventies

BY Marvin Bell

His army jacket bore the white rectangle

of one who has torn off his name. He sat mute

at the round table where the trip-wire veterans

ate breakfast. They were foxhole buddies

who went stateside without leaving the war.

They had the look of men who held their breath

and now their tongues. What is to say

beyond that said by the fathers who bent lower

and lower as the war went on, spines curving

toward the ground on which sons sat sandbagged

with ammo belts enough to make fine lace

of enemy flesh and blood. Now these who survived,

who got back in cargo planes emptied at the front,

lived hiddenly in the woods behind fence wires

strung through tin cans. Better an alarm

than the constant nightmare of something moving

on its belly to make your skin crawl

with the sensory memory of foxhole living.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/50571/veterans-of-the-seventies?mc_cid=af276c027e

A Phosphorescence

by James Cervantes

I discovered phosphorescence one day

clearing pine needles from an acre plot

in the mountains. I raked and scratched

large piles, then became obsessed with the base

of one tree, raking harder and deeper until black,

matted clumps of needles came up to reveal a glow.

Fire, I thought, afraid for the forest. But no smoke,

no burn smells. There could be light without fire,

like that moment of warmth I mistook for fire,

a gentle touch on your arm that was light

and would be no more than that.

“‘A poem thirty-five years in the making,’ a blurb might read. In truth, my witnessing of ‘A Phosphorescence’ occurred thirty-five years ago, much as described in the poem’s first eight lines. Year after year, I would write out the experience but would then get stuck. Last year, I revisited the definition I found online: ‘light emitted by a substance without combustion or perceptible heat;’ [but this time I read its application] in physics: ‘the emission of radiation in a similar manner to fluorescence but on a longer timescale.’ So that emission continues after excitation ceases. Finally, I had the poem!”

—James Cervantes

Hey everyone, I’m #newhere. I’m interested in #blackmetal, #brazil, #celtic, #death-doom, #deathmetal, #doom-metal, #dublin, #epic, #esoteric, #gaelic, #gaelic-folk-rock, #heavy-metal, #httpsdiasporasocialnetstream, #ireland, #literature, #music, #occult, #orion, #pagan, #pagan-metal, #poetry, and #radio.

HAIKU

by petro c. k.

it’s all over

but the counting

distant sirens

—from Poets Respond

petro c. k.: “As one who often writes haiku, it’s always a challenge to distill moments to its essence. When I was sitting with my thoughts, I heard sirens off in the distance, which captured the sense I had of melancholy, anxiety, and unknown dangers on the horizon.”

Happy Birthday Anne Sexton!!

Her Kind

By Anne Sexton

I have gone out, a possessed witch,

haunting the black air, braver at night;

dreaming evil, I have done my hitch

over the plain houses, light by light:

lonely thing, twelve-fingered, out of mind.

A woman like that is not a woman, quite.

I have been her kind.

I have found the warm caves in the woods,

filled them with skillets, carvings, shelves,

closets, silks, innumerable goods;

fixed the suppers for the worms and the elves:

whining, rearranging the disaligned.

A woman like that is misunderstood.

I have been her kind.

I have ridden in your cart, driver,

waved my nude arms at villages going by,

learning the last bright routes, survivor

where your flames still bite my thigh

and my ribs crack where your wheels wind.

A woman like that is not ashamed to die.

I have been her kind.

one of my favorites (it's like all my dreams/nightmares) and basis of Peter Gabriel's Mercy Street

45 Mercy Street

by Anne Sexton

In my dream,

drilling into the marrow

of my entire bone,

my real dream,

I'm walking up and down Beacon Hill

searching for a street sign —

namely MERCY STREET.

Not there.

I try the Back Bay.

Not there.

Not there.

And yet I know the number.

45 Mercy Street.

I know the stained-glass window

of the foyer,

the three flights of the house

with its parquet floors.

I know the furniture and

mother, grandmother, great-grandmother,

the servants.

I know the cupboard of Spode

the boat of ice, solid silver,

where the butter sits in neat squares

like strange giant's teeth

on the big mahogany table.

I know it well.

Not there.

Where did you go?

45 Mercy Street,

with great-grandmother

kneeling in her whale-bone corset

and praying gently but fiercely

to the wash basin,

at five A.M.

at noon

dozing in her wiggy rocker,

grandfather taking a nap in the pantry,

grandmother pushing the bell for the downstairs maid,

and Nana rocking Mother with an oversized flower

on her forehead to cover the curl

of when she was good and when she was…

And where she was begat

and in a generation

the third she will beget,

me,

with the stranger's seed blooming

into the flower called Horrid.

I walk in a yellow dress

and a white pocketbook stuffed with cigarettes,

enough pills, my wallet, my keys,

and being twenty-eight, or is it forty-five?

I walk. I walk.

I hold matches at street signs

for it is dark,

as dark as the leathery dead

and I have lost my green Ford,

my house in the suburbs,

two little kids

sucked up like pollen by the bee in me

and a husband

who has wiped off his eyes

in order not to see my inside out

and I am walking and looking

and this is no dream

just my oily life

where the people are alibis

and the street is unfindable for an

entire lifetime.

Pull the shades down —

I don't care!

Bolt the door, mercy,

erase the number,

rip down the street sign,

what can it matter,

what can it matter to this cheapskate

who wants to own the past

that went out on a dead ship

and left me only with paper?

Not there.

I open my pocketbook,

as women do,

and fish swim back and forth

between the dollars and the lipstick.

I pick them out,

one by one

and throw them at the street signs,

and shoot my pocketbook

into the Charles River.

Next I pull the dream off

and slam into the cement wall

of the clumsy calendar

I live in,

my life,

and its hauled up

notebooks.

To David, About His Education

By Howard Nemerov

The world is full of mostly invisible things,

And there is no way but putting the mind’s eye,

Or its nose, in a book, to find them out,

Things like the square root of Everest

Or how many times Byron goes into Texas,

Or whether the law of the excluded middle

Applies west of the Rockies. For these

And the like reasons, you have to go to school

And study books and listen to what you are told,

And sometimes try to remember. Though I don’t know

What you will do with the mean annual rainfall

On Plato’s Republic, or the calorie content

Of the Diet of Worms, such things are said to be

Good for you, and you will have to learn them

In order to become one of the grown-ups

Who sees invisible things neither steadily nor whole,

But keeps gravely the grand confusion of the world

Under his hat, which is where it belongs,

And teaches small children to do this in their turn.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/52813/to-david-about-his-education

OUR WAITRESS’S MARVELOUS LEGS

by Grace Bauer

It’s men I’m prone to eye, but when she comes

to take our order, I’m too distracted

to think beyond drinks, too awed

by the ink that garments her limbs

to consider appetizers, much less entrees.

It’s not polite to stare, I know,

but the fact of her invites it.

Why else the filigreed ankles,

those Peter Max planets orbiting her

left shin, that Botticelli angel soaring

just below her right knee?

She’s a walking illustration, adorned

to amaze, yet as seemingly nonchalant

as the homely white-sneakered HoJo girl

I myself once was, describing the specials

of the day, listing our options for dressings,

then scribbling the choices we make

on her hand-held pad.

My companion can’t help wondering how far

up the ante goes, says he bets there’s a piercing

or two at the end of the, so to speak, line.

I’m more inclined to ponder motivation

and stamina—how long and how much

she suffered to make herself a work of art.

For I have no doubt, she sees her own flesh

as a kind of canvas. Her body as frame

and wall and traveling exhibition,

a personal statement on public display.

Same could be said of the purple tights

I wear beneath my frilly black skirt—

too bold a choice for some people’s tastes,

but not a permanent commitment.

Clothes make the woman more

than the man, despite the familiar adage,

and body as both self and other is

a contradiction we live with, however comfortably

—or not—we grow into our own skins.

I’ll admit part of what I feel

is admiration, even envy.

Whatever she may ever become

in this world, she will never again be drab.

She’ll wear this extravagance

of color and form as she grays

into more—or less—wisdom.

But tonight she simply performs

her duty as server, courteous and efficient

as she does what she can to satisfy

the hunger we walked in with, but not

the hunger the sight of her

inspires us to take home.

—from Rattle #36, Winter 2011

https://www.rattle.com/our-waitresss-marvelous-legs-by-grace-bauer/

#mybook #dylan #books #literature #music

November 8, 2024. Thursday

Knocking On Heaven’s Door ~ Dylan

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O-sVpVIovKk

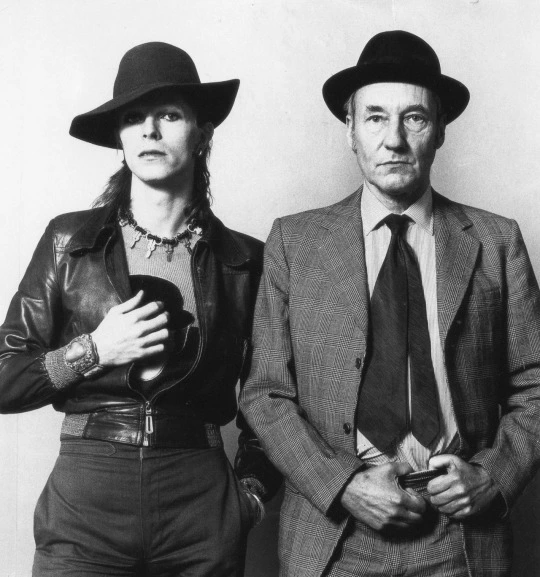

David Bowie and William S. Burroughs.

© Terry O’Neill, 1974.

#photo #foto #music # #bowie #burroughs #author #literature #rock

Dating in the Apocalypse Bunker

By Kristen Mears

You take the lamp with your last battery

and meet me at the radios, where it’s quiet,

and we can be alone. I like how the light dims

and flickers, the way it plays across the steel.

I like how we can’t see the sand in the air.

You hold my gloved hand in your gloved hand

and we walk the hydroponic halls. I love you

because your eyes are green, because we eat

protein cans and you tell me about birds,

how your dad still has grass in his vault.

And we’re dressed to the nines, in our cleanest

boots, the dust scrubbed from our tanks

until they gleam. Our utility suits are beeping

beneath our helmet read-outs, but no longer

are we clumsy, like those men who fled to Mars.

And we go not to the movies but to the oxygen

chambers, where we crouch low, lean close

to a vent. You shed your gear first, lips dry

and desert-cracked, and we share that same

recycled air, press our mouths against the wall,

breathe so deeply we see stars.

https://www.palettepoetry.com/2024/10/21/dating-in-the-apocalypse-bunker/