If artificial intelligence had started with emotional affect instead of vision (or language?), everything would have been different, says neuroscientist Mark Solms. Well, it is true that efforts to process vision go back to the earliest days of AI, and took a quantum leap forward with AlexNet winning the ImageNet competition using neural networks in 2012. But efforts to master language and beat the Turing Test also date back to the earliest days of AI. How could the AI field have started with emotional affect? By studying the reticular activating system of the brain? How could that have been done?

"Had we not started with vision, but rather had started with affect, the whole brouhaha would never have happened, because the problem with vision is that it is not an intrinsically conscious process. The famous knowledge argument of Frank Jackson, which I don't need to spell out,

"My simplified version of the knowledge argument is that there's this imaginary visual neuroscientist named Mary, and she knows that's the knowledge. She knows everything there is to know about the physics and physiology and anatomy and information science of vision." "But she's blind. So although Mary knows everything about the functional causal mechanisms of visual processing, she's never experienced what it is like to see. So now, one day, thanks be to God, the gift of sight is bestowed on Mary. And Jackson's point is, at that moment she learns something utterly new about vision, namely, what it's like to experience redness and greenness and contrast and light and dark and so on."

He comments on the AI field's pursuit of "cortical" processing:

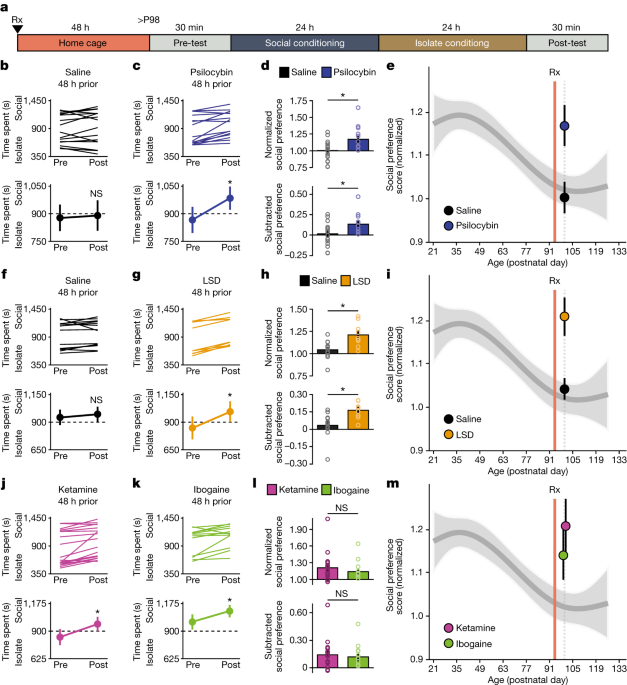

"If the cortex were the seat of consciousness, then there's a very simple prediction, which is that if you remove the cortex, you should remove consciousness. You know what could be more straightforward than that in terms of popperian science? You're saying, okay, I have an hypothesis that the cortex is the seat of consciousness, and that here is a falsifiable prediction. The prediction is remove cortex. You should remove consciousness. Problem is, that doesn't happen if you remove cortex, as has been done thousands of times in neonatal mammals. The animal doesn't fall into a coma. In other words, it doesn't lose consciousness. It wakes up in the morning, goes to sleep at night. But much more important than that, it is emotionally responsive to its environment. So these these decorticate animals play.They fight. They flee, when in danger. They copulate. They raise their pups to maturity. You know, all of this and and of course, we're talking about animals. But the same applies to human beings, that there are children who are who are born with a condition called hydranencephaly, which basically means a cranium filled with cerebrospinal fluid instead of a cranium filled out with, with cortex. They have no cortex. And just like the neonate decorticate mammals, these neonate decorticate humans, they wake up in the morning, go to sleep at night, they have seizures, they lose consciousness. But much more importantly, they are emotionally responsive to their environments. You tickle them, they giggle. You give them something that they like, they are pleased. You take it away, they're annoyed. They arch their back. They protest, you give them a fright, they startle, etc. none of which is predicted by the theory that the cortex is the seat of consciousness."

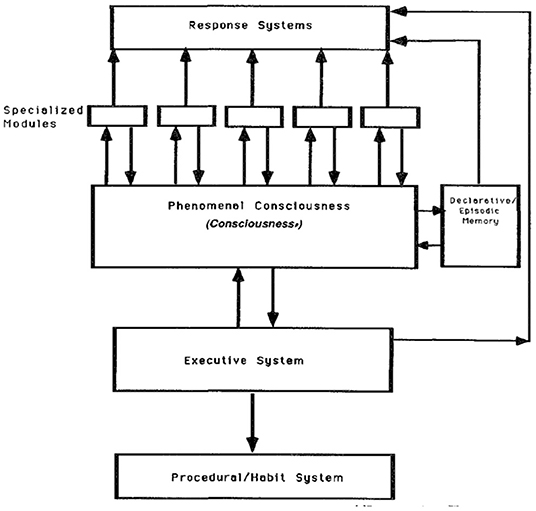

"The standard theory is that consciousness can be divided into two aspects. The one is its contents or qualities. And that's what the cortex provides, and the other is its sort of level or, or quantities. And that's what the brainstem provides. That's the standard view. In other words, if you have only a brainstem and you do not have a cortex, you should have wakefulness, a kind of blank wakefulness. You should be in a condition that we recognize in neurology as the vegetative state, in other words, which is another name for the vegetative state, nonresponsive wakefulness. And that's what you predict on that theory. And yet these kids are not nonresponsive, if you will, give the double negative. They are responsive. They are emotionally responsive. So the theory is just, you know, the prediction arising, the most basic prediction arising from the theory that the cortex is the seat of consciousness, of its contents and its qualities is falsified."

"If you stimulate those brainstem structures that I'm talking about, the reticular activating system, and by the way, there's also another structure called the periaqueductal gray. If you stimulate these structures electrically, there's again a very straightforward prediction. If all that they do is volume control, you know, they just regulate the level of wakefulness." "Then if you stimulate them, you might see the patient becoming more alert or less alert or, you know, falling into a coma or moving into a into a highly vigilant and aroused state. But there shouldn't be any content or quality to that."

"What you see is intense affective states, depending on which part of the reticular activating system or periaqueductal gray you stimulate. You generate a wide variety of the most intense affective states, and you see nothing like that when stimulating cortex. If you stimulate cortex, you get barely any affective responses. If you do, it's kind of like memories of affects or thoughts about affects or abstractions about affects. You don't get the intense, actual raw feelings that you do. So that's weighty evidence that the electric electrical stimulation evidence is weighty support for the idea that affect is actually generated by these brainstem structures, because you were just arguing that the the reticular activating system and the periaqueductal gray is the the seat of arousal and therefore the seat of affect and the seat of consciousness."

Rethinking the Mind - Prof. Mark Solms - Machine Learning Street Talk

#solidstatelife #ai #neuroscience #consciousness