All Things Must Balance

An interesting look at the relation between the philosophy of economics and more general world views of medieval Europe. Doesn't really address the root causes and often reads like the "pseud's corner" snippets in Private Eye, using unnecessary pseudo-intellectual rhetoric which makes simple statements become overly-complicated for no reason. Still, interesting.

How does the definition of what is ‘natural’ shift radically within an intellectual culture? How does the unthinkable become thinkable – the unimaginable imaginable? What is it that causes vital new questions to rise to the surface and potent new answers to be envisaged and argued?

Well, let's start with economics.

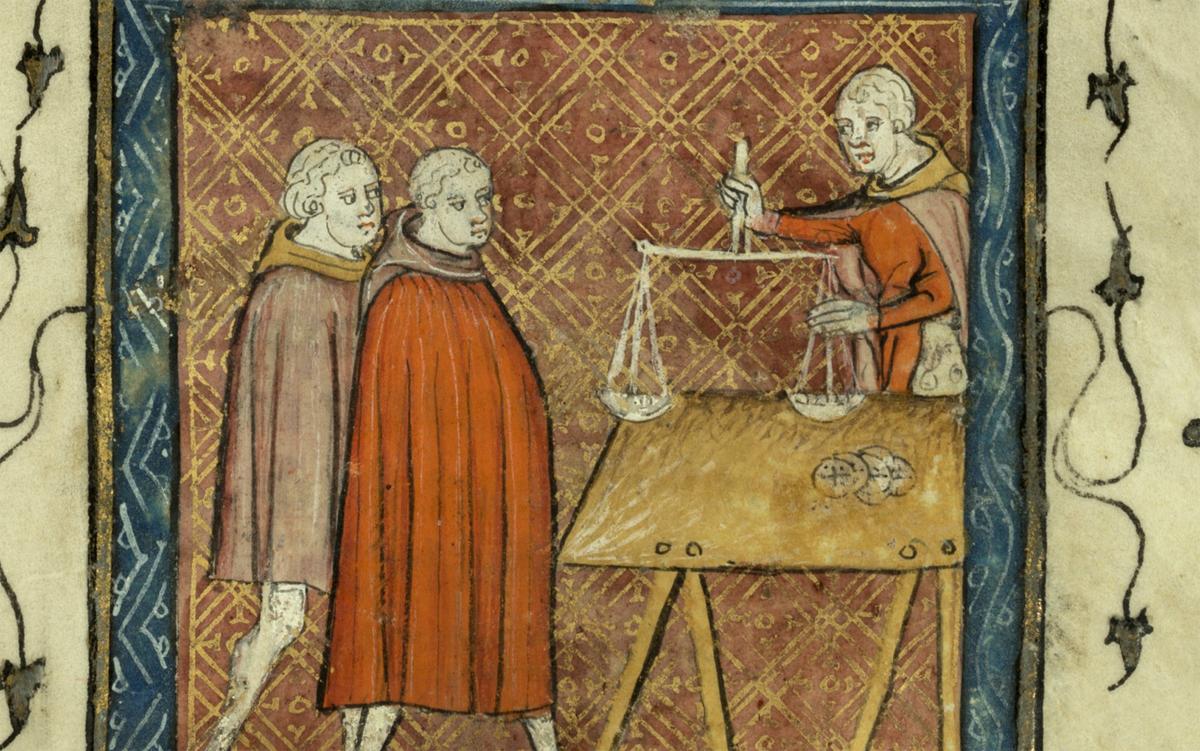

At the root of traditional usury theory lay the demand for the maintenance of a perfect one-to-one equality between exchangers: for the lender to demand back from the borrower even one penny more in return was defined as manifest usury... Medieval writers employed many rationalisations to condemn usury and to insist that any violation of one-to-one equality in the loan is tantamount to a violation of both the divine and the natural order. Of these, the most common held that money is inert and sterile by its nature and, therefore, for money to grow by itself or to multiply itself still represents a clear violation of the natural order, instituted by God.

I guess they saw money as like animals ? God wouldn't allow anything to go extinct, and apparently money was the same thing. The past is certainly a foreign country. Anyway, this couldn't last :

True, he Godfrey [of Fontaines] admits, in most contracts of buying and selling, neither party can ever know, for certain, the value of the goods they are exchanging. Nor can they know, at the time of exchange, which party might benefit more from the exchange in the long term. Doubt, he recognises, is inescapable. Yet Godfrey was suddenly able to imagine, and to argue, that the very condition of shared uncertainty in itself produces an aequalitas sufficient to render exchanges licit and non-usurious. The unshakeable requirement for aequalitas in exchange has been met, he argues, as long as there exists an equal measure of doubt on the part of both buyer and seller.

In utter contrast to traditional claims for the sterility of all money, Olivi asserts that money, when in the form of commercial capital, is naturally fruitful, expansive and capable of multiplying, in its essence... Olivi has come to recognise that it is the very nature of capital to multiply, he judges that merchants who buy and sell money for a fluctuating agreed-upon price do so without committing a sin against either nature or God, and thus, without committing the sin of usury.

And from medieval economic theory we turn a corner into something very different.

He [Jean Buridan] then reasons that, given the spherical nature of the Earth, and given that all earth falls naturally toward the Earth’s centre (as Aristotle maintained), and given the great over-abundance of water with respect to land and, finally, assuming along with Aristotle that the Universe is eternal, he is led to ask why, in the fullness of time, should any portion of land remain dry above the waters and habitable?

It's all very Olber's Paradox, but with geology instead.

To answer this question, indeed, even to ask this question, Buridan imagines the whole of Earthly nature as an integrated physical system in dynamic equilibrium (to put it in modern terms). He then invents an elaborate physical explanation, which, as he writes, ‘seems probable to me and by means of which all appearances could be perpetually saved.’ He views the totality of geological displacement over eternity as a grand self-balancing system, functioning entirely on physical principles. As a consequence, he speculates that while parts of earth are being continually washed into the sea at multiple parts of the globe, an identical quantity of earth is being raised above the circle of the waters at other parts, eventually accumulating there to produce the very same mountainous heights that are being worn down elsewhere. Indeed, he explains the current existence of high mountains on Earth as the natural product of the perpetual cycle of erosion and accumulation in eternal equilibrium.

#History

#Philosophy

#Economics

#Geology

https://aeon.co/essays/how-socioeconomic-equalisation-generates-new-ideas-of-balance