#armenia

When interrogating activists, Russian #cops sometimes ask whether you support “the Ukrainian #ideology”. You inevitably wonder what that is. It happens that an activist replies with a counterquestion: “What do you mean by ‘the Ukrainian ideology'”? And the enforcer of Russian law says: “You must know. You are an educated person, aren’t you?”

Is there an English, French or Spanish ideology? The French one is claimed to exist. As one emigrant said, “It is #liberty, #equality, fraternity and #secularity (the #church has no dominance over principles of secular humanism). This is literally an official formula”. However, a question remains of why a certain nation became for Russians a personification of any ideology. Since the #USSR collapsed, no other former republic of the union has become such a personification. A Nihilist reporter talked with Ukrainians and Russians about this phenomenon and the peculiarities of #police mentality.

There is an opinion that Russians believe the very idea of the existence of the Ukrainian language and #culture, as well as of an independent Ukrainian state, to be a hostile ideology. Some argue that the police, out of their ignorance, simply do not understand the meaning of the term, confusing “ideology” with #pacifism, #humanism or who knows what.

https://www.nihilist.li/2022/09/01/in-the-eyes-of-imperialists-what-is-the-ukrainian-ideology/ #repression #russia #lgbt #armenia #ukraine #imperialism #nationalism

The Pre-1895 Censuses in Ottoman Empire

The first attempt to conduct a census in Turkey was made in 1844 by Rıza Pasha , the minister of war. It showed that there were some 2 million Armenians in Asiatic Turkey.

In 1867, the Turkish government commissioned publication of a volume on Turkey for the Universal Exposition in Paris. It, too, indicated that there were 2 million Armenians in Asia Minor and another 400,000 in European Turkey.

On the eve of the Congress of Berlin, the Patriarchate drew up a preliminary balance based on the empire’s official Salname for the year 1294 of the Hegira (1878). It put the number of Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire in this period at 3 million : 400,000 in European Turkey (primarily in Constantinople, Thrace, Bulgaria, and Rumania); 600,000 in western Asia Minor (the vilayets of Angora, Aydın/ Smyrna, Konya, Adana, Aleppo, the mutesariflik of Ismit, etc.); 670,000 in the vilayets of Sıvas, Trebizond, Kayseri, and (southern) Dyarbekir; 1,330,000 on the Armenian plateau – that is, in the vilayets of Erzerum (excluding the regions annexed by Russia) and Van – as well as the northern part of the vilayet of Dyarbekir, comprising the districts of Harput, Eğin, Arapkir, and Arğana on the one hand and, on the other, the northern part of the sancak of Siirt, comprising the Sasun, Şirvan, and Hizan districts.

Population Erzerum and Van Dyarbekir (North) Total

Armenians 1,150,000 180,000 1,330,000

Turks 400,000 130,000 530,000

Kurds 80,000 40,000 120,000

Greeks 5,000 – 5,000

Chald-Syriacs 14,000 8,000 22,000

Zazas 35,000 2,300 37,300

Yezidis 13,000 2,000 15,000

Gypsies 3,000 – 3,000

Total 1,700,000 362,300 2,062,300

Oddly, the “official” census results published by Kemal Karpat provide radically different estimates for the years 1881/82–1893, a period during which the administrative organization of the Armenian provinces was considerably modified: almost all the former mutesarifliks of Chaldir, Kars and Bayazid now came under Russian rule, while the boundaries of the eyalets of Erzerum and Dyarbekir were redrawn.

According to these documents, the Armenian population was distributed as follows: there were 179,645 Armenians in European Turkey (156,032 of them in Constantinople, 270,183 in western Asia Minor – the vilayets of Angora, Aydın, Konya, Adana, and Aleppo, the mutesariflik of Ismit, and elsewhere); 227,202 in the vilayets of Sıvas, Trebizond, and Dyarbekir (not including the northern part of the Dyarbekir vilayet) and the sancak of Kayseri; and 371,113 in Erzerum, Bitlis, Van, Harput, and the northern part of the vilayet of Dyarbekir. The Armenian population of the five vilayets was divided up as follows:

Erzerum 107,868 ****

Bitlis 106,306

Dyarbekir 22,464 ****

Harput 75,093

Van 59,382

Total 371,113

Muslims

Erzerum 445,548 ****

Bitlis 167,054

Dyarbekir 101,065

Harput 300,188

Van 54,582

Total 1,068,437

Alongside these figures, we may range two other sets of statistics obtained in the same period. First, those of the Armenian Patriarchate, which date from 1878/79:

Provinces Armenians

Erzerum 280,000

Bitlis 250,000

Dyarbekir 150,000

Harput 270,000

Van 400,000

Total 1,350,000

Second, Cuinet ’s statistics, culled around 1890 from the Salname and other documents furnished by the Ottoman administration:

Population Erzerum Bitlis Dyarbekir Harput Van Total

Armenians 135,087 131,390 83,226 69,718 80,000 499,421

Muslims 500,782 257,863 388,644 504,366 241,000 1,892,655

Gr. and Syr. 3,725 210 53,420 650 99,785 157,790

Total 639,594 389,463 525,290 574,734 420,785 2,549,866

An examination of the figures presented above reveals wide disparities. Thus, from 1844 to 1867, official Turkish sources affirm that there were 2,400,000 Armenians living in the empire, with 2,000,000 of them in Asiatic Turkey. In the census carried out between 1881 and 1893, however, the number of Armenians suddenly falls by one-half, to 1,048,143 (156,032 of them in Constantinople). Unless we assume that these figures resulted from political manipulation, it is hard to explain so great a difference from one census to the next, even if we take into account the 1878 loss of Kars and Ardahan and the exodus of several tens of thousands of Ottoman Armenians to Russia.

The Salname of 1294/1878 that the Armenian Patriarchate presented to the Congress of Berlin was a no less official Ottoman document. Produced for economic purposes before these “adjustments” had been made, it would seem to reflect the demographic evolution of the region much better: it puts the number of Armenians in Turkey at 3 million. This figure indicates a 25 per cent population increase over 30 years, as opposed to the decrease of 50 per cent reported in the other official Ottoman statistics.

Similarly, for the Armenian plateau as we have defined it above, the Ottoman census of 1881–93 gives figures of 1,068,437 Muslims and 371,113 Armenians out of a total population of 1,500,000, whereas the statistics published in the 1294/1878 Salname presented by the Patriarchate in Berlin are quite different: they show 1,330,000 Armenians, 650,000 Kurds and Turks, 27,000 Greeks and Christian Syriacs, and 55,300 Zazas, Yezidis, and Gypsies.

If we put Turks, Kurds, Zazas, Yezidis, and Gypsies in the same category – although the Gypsies were often Christians – as the Ottoman administration probably did, then we arrive at a figure of 705,300 out of a total 2,062,300 inhabitants. But we still fall far short of the total, even when we compare the Ottoman census to that conducted by the Patriarchate in 1882.

The Patriarchate’s census, which takes into account the fact that the Armenians of Kars and Ardahan had come under Russian rule in 1878, indicates that 1,350,000 Armenians were still living in the eastern provinces in this period. Attentive examination of Salaheddin Bey’s statistics throws some light on this question. They state that a total of 13,223,000 Muslims lived in all of Asiatic Turkey out of a total population of 16,383,000.

Of this total, 10,907,000 people lived in western and central Anatolia and Cyprus – 1,000,000 were Greek, 80,000 Jewish, 700,000 Armenian, and 9,127,000 Muslim. In Syria and Iraq, 2,650,000 Arabs, Turks, Druze, and Kurds lived side by side with 100,000 Christians, while 900,000 Arabs inhabited the Hejaz and Yemen.

If we add up these figures, it appears that, of the 13,223,000 Muslims said to be living in Ottoman Asia, 12,677,000 lived outside the boundaries of the “Anatolian East,” which, according to Salaheddin Bey, had a total population of 1,906,000. Subtracting, we find that this province, comprising the vilayets of Van, Erzerum, Kurdistan, and Harput, was inhabited by 1,300,000 Armenians, 60,000 other Christians, and 546,000 Kurds, Turks, Turkomans, Çerkez, and so on.

The Ottoman statistics in the 1294/1878 Salname submitted by the Armenian patriarch to the Congress of Berlin differ only slightly from these figures. They show a total of 1,330,000 Armenians, 650,000 Kurds, Turks, and so on, as well as 82,000 people belonging to diverse other groups (taking only northern Kurdistan in the vilayet of Dyarbekir into account). The census carried out by the Patriarchate in 1882 arrived at a similar result: it indicated that 1,350,000 Armenians were living in this region.

Once again, the official Salnames vouch for the credibility of the Armenians’ censuses. The 1298/1882 Salname published the state budget figures for 1296/1880 as established by the Council of Ministers. This document indicated that the tax known as the bedeliaskeri, paid by all non-Muslim males between the ages of 15 and 60, showed an annual yield of 462,870 Turkish pounds for all of Turkey.

However, the Council of Ministers estimated, according to the same document, that this tax should have yielded twice as much. Implicitly, the state thus acknowledged that it collected this tax from only half of its non-Muslim population – the half reported in its census. While it is an established fact that the official statistics were falsified, it is important to determine the extent of the falsification. In the case to hand, only an examination of all the regions concerned would allow us to establish the actual dimensions of the fraud. Such an examination could, for example, provide irrefutable evidence of a substantial Armenian population, which the 1891–93 Ottoman census ignores or minimizes.

Among the obvious falsifications, we can cite the Ottoman figures for Scutari, which indicate that no Armenians lived in the area,13 even though it is known that entire neighborhoods were inhabited by these Christians and that there were many churches and schools there.14 In Mersin, in the heart of Cilicia, the Ottomans counted 438 Armenians and 19,737 “Muslims.”15 In the kaza of Zyr, near Angora, the Turkish census put the number of Armenians at 2,214, although the village of Stanoz alone, inhabited exclusively by Armenians, had a population of 3,000.

Note- this chapter is from Raymond Kévorkian ’s book ARMENIAN GENOCIDE: A Complete History , pp. 267-269.

Map- H. Hepworth, Through Armenia on horseback, London, 1898, Erzurum

Source - http://www.houshamadyan.org/arm/mapottomanempire/erzurumvilayet.html

The post The Pre-1895 Censuses in Ottoman Empire appeared first on Aniarc.

#armenia #diaspora #publications #turkey #featured #raymondkévorkian #thearmeniangenocide #thepre1895censusesinottomanempire

Here are the 37 nations that chose not to condemn Russia's invasion of #Ukraine in a UN vote on March 2nd.

This is interesting as it is strongly suggestive of Russia's global allies.

#Russia #allies #unitednations #vote #unvote #Algeria #Angola #Armenia #Bangladesh #Belarus #Burundi #CentralAfricanRepublic #China #Congo #Cuba #EquatorialGuinea #Eritrea #India #Iran #lraq #Kazakhstan #Kyrgyzstan #Lao #Madagascar #Mali #Mongolia #Mozambique #Namibia #Nicaragua #NorthKorea #Pakistan #Senegal #SouthAfrica #SouthSudan #SriLanka #Sudan #Syria #Tajikistan #Uganda #Uzbekistan #Vietnam #Zimbabwe #maps #data

Armenia’s miserable dilemma

Armenians see themselves in a lose-lose situation, where Armenia could lose its last hopes for sovereignty if Russia wins in Ukraine, while if it loses, the legitimacy of its peacekeepers in Karabakh may be questioned.

Matosavank, 13th century is small church hidden in a forested area of Dilijan National Park. The church is currently in ruins and is difficult to find.

Forgotten and hidden in the forests of Armenia

More information on Wikipedia...

Exterior view of Matosavank

Matosavank Church of Surb Astvatsatsin of Pghndzahank,1247

© Travis K. Witt

For my treasured and beloved @Aline ♥ ♥ ♥ and oc all #Armenia #lover...

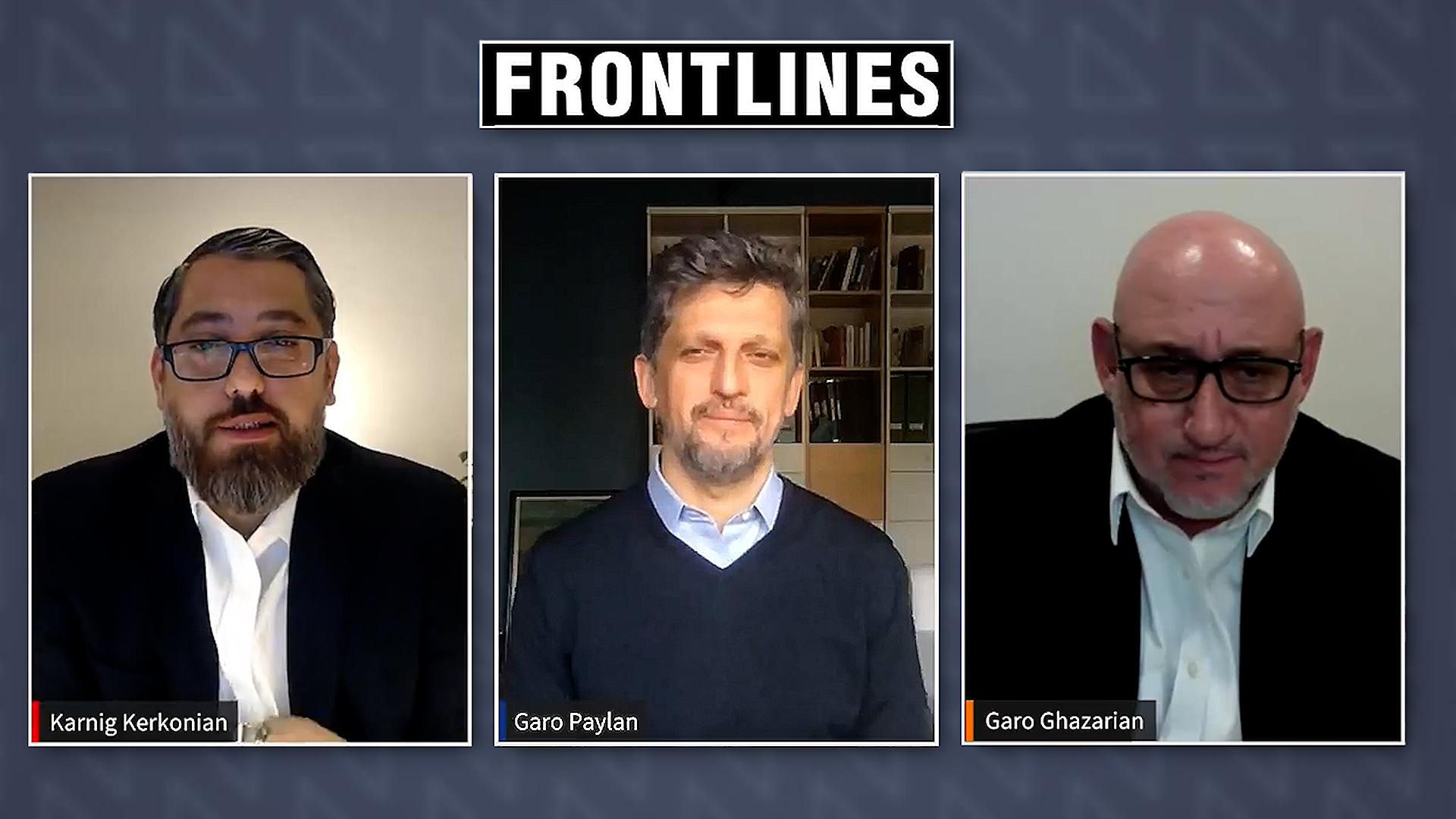

Garo Paylan on what’s next for Armenia-Turkey relations

In the latest edition of Frontlines, Karnig Kerkonian and Garo B. Ghazarian speak to Garo Paylan, an Armenian member of the Turkish parliament, to discuss the developing nature of Armenia-Turkey relations, prospects for normalization and more.

The post Garo Paylan on what’s next for Armenia-Turkey relations appeared first on CIVILNET.

What do Russia-Ukraine tensions mean for Armenia?

In the latest edition of Insights With Eric Hacopian, Eric discusses the impact of Russia-Ukraine tensions on Armenia. He also unpacks the recent updates related to the Armenia and Turkey normalization process.

The post What do Russia-Ukraine tensions mean for Armenia? appeared first on CIVILNET.

The importance of Armenia’s case in the World Court

In the latest edition of Frontlines with Karnig Kerkonian and Garo B. Ghazarian, international law experts Levon Gevorgyan and Yeghishe Kirakosyan discuss the latest developments to come out of Armenia v. Azerbaijan case at The Hague. Kirakosyan, who is one of the Armenia representatives to the International Court of Justice, also discusses why cases like these are important for Armenia.

The post The importance of Armenia’s case in the World Court appeared first on CIVILNET.

Armenia’s ruling party goes after democratically-elected mayors in multiple cities

- Yerevan’s City Council will convene for a session on the mayor's impeachment on Tuesday.

- Southern railway network between Armenia and Azerbaijan to be completed in two to three years, says Pashinyan.

- The IMF forecasts a 5.5% economic growth rate in Armenia in 2021.

The post Armenia’s ruling party goes after democratically-elected mayors in multiple cities appeared first on CIVILNET.

● NEWS ● #RTL ☞ Can #Turkey and #Armenia really mend their hostile ties? https://today.rtl.lu/news/world/a/1834112.html

Unpacking the Pashinyan-Aliyev meeting in Brussels

During a meeting in Brussels on December 14, the leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan reached a consensus regarding the reopening of railway networks between the two countries. One point of contention remains Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev’s demand that the access route through Armenia’s south to its exclave of Nakhichevan be customs free. Azerbaijan insists that if this is rejected, Armenians will have to pass through Azerbaijani customs to reach Nagorno-Karabakh.

Credits: Ruptly

The post Unpacking the Pashinyan-Aliyev meeting in Brussels appeared first on CIVILNET.

https://twitter.com/Deport_Alarm/status/1470754821208690695

#Pakistan #Kazakhstan #Georgia #Armenia #Nigeria #StopDeportation #Sammelabschiebung

‼️TODAY 4⃣ MASS-DEPORTATION CHARTERFLIGHTS‼️

— Deportation Alarm (@Deport_Alarm) December 14, 2021

🟡 Frankfurt to #Pakistan

🟡 Berlin to #Kazakhstan

🟡 Leipzig-Halle to #Georgia

🟡 Köln-Bonn to #Armenia

And a 5th planned charterflight to #Nigeria was canceled.

More info: https://t.co/fS1ot0cwQt#StopDeportation #Sammelabschiebung

French presidential candidate calls Armenians “model of resistance”

- 211 new buses start operating in Yerevan.

- 2022 French presidential candidate Eric Zemmour visits Armenia.

- The Armenian government has seemingly hidden details regarding water price increase.

The post French presidential candidate calls Armenians “model of resistance” appeared first on CIVILNET.

Armenia’s ruling party wins election in most of the municipalities, but loses major cities

On December 5, elections were held in 36 communities of Armenia. The results are known.

The post Armenia’s ruling party wins election in most of the municipalities, but loses major cities appeared first on CIVILNET.

Is the remedial secession of Nagorno-Karabakh a good idea?

Nerses Kopaylan, Professor of Political Science at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, talks to CivilNet’s Eric Hacopian about the prospects of Nagorno-Karabakh’s remedial secession from Azerbaijan and whether this would be desirable for the Armenian side. Professor Kopaylan compares and contrasts this outcome with the remedial secession of Kosovo and why this could help deal with the issue of self-determination and sovereignty.

The post Is the remedial secession of Nagorno-Karabakh a good idea? appeared first on CIVILNET.

“Logic of corridors” rejected again in Sochi statement, says Armenian official

- Azerbaijai forces have withdrawn from the Ishkhanasar section of Armenia’s Syunik region, according to unofficial reports.

- The “logic of corridors” was once again refuted in the November 26 Pashinyan-Aliyev-Putin statement, says Armenian official.

The post “Logic of corridors” rejected again in Sochi statement, says Armenian official appeared first on CIVILNET.

#armenia #dailyarmenia #politics #region #reportsinenglish #armeniaazerbaijan2021 #armeniaborder #armeniacorridor #armenianterritory #azerbaijanattack #azerbaijancorridor #ishkhanasar #syunikazerbaijan #zangezurcorridor