#Quote In the late 1990s, #Irish #priest #Malachi #Martin gave a number of #interviews in which he claimed that the Third Secret of #Fatima was connected to #Russia and #Kiev.

Source: https://youtube.com/watch?v=Rdzt0AsATLM

One person like that

#Quote In the late 1990s, #Irish #priest #Malachi #Martin gave a number of #interviews in which he claimed that the Third Secret of #Fatima was connected to #Russia and #Kiev.

Source: https://youtube.com/watch?v=Rdzt0AsATLM

https://yewtu.be/watch?v=saE-OQlXtno

https://www.democracyatwork.info/eu_noam_chomsky_fragile_us_empire

#ProfWolff gives updates on #US #freight #workers #strike #preparations; #progressives and #labor targeting #municipal #government; #Chipotle #store-closing to stop #unionizing, and #OccupyWallStreet's " #Debt-Collective" $5.8 billion #student-loan-forgiveness #win. In the second half of the show, Prof. Wolff #interviews #NoamChomsky on the #decline and #fragility of the #US #empire, the role of US #military and the rise of #fascism as a coping mechanism.

#economic #update #prof #richardwolff #rdwolff #wolff #chomsky #fragile #audio

#kraspop #chronique #fanzine dans #B.R.A. #zine

dans leur 12ème numéro qui vient de partaitre,

Dans les #interviews et #reviews : ça parle de #zik

et #culture #punk #oi! #reggae #soul #rock

ainsi que de culture #populaire aussi,

par exemple de #pif et de #polar

pour commander BRA zine :

fanzinebra@hotmail.com (2€+ 2 timbres)

n'hésitez pas à lui demander quels autres zines il a en #distro sinon !

très bon reportage sur arte sur les #musics #électroniques du début a maintenant avec des #interviews des différents protagonistes de la #scène techno #house

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pBXeFMX8jXc

#musique

Bangladeshi architect Marina Tabassum, who was recently awarded the Soane Medal, explains why she only works in her home country in this exclusive interview.

Tabassum is known for designing buildings that use local materials and aim to improve the lives of low-income people in Bangladesh, where all her projects are based.

"The reason I've never really worked outside Bangladesh is the fact that wherever I work, I must understand that place, it is very important to me," Tabassum told Dezeen in a video call from her studio in Dhaka.

"To go somewhere and build something without having the full knowledge of it makes me quite uncomfortable," she added.

Marina Tabassum's designed the underground Museum of Independence in Dhaka. Photo is by FM Faruque Abdullah Shawon

Marina Tabassum's designed the underground Museum of Independence in Dhaka. Photo is by FM Faruque Abdullah Shawon

As Tabassum feels the need to have a connection to the spaces she designs, she doesn't see any reason to create buildings outside of her home country.

"We have so much to do in Bangladesh, we have a lot of work that's there," she said. "I really do not feel the need to go anywhere else to look for work – we all have our own places to concentrate on."

"In a lifetime there's only so much you can do, so staying focused is probably more important," she continued.

Among her designs in Bangladesh are the country's Museum of Independence and the adjacent Independence Monument, as well as the Aga Khan Award-winning Bait Ur Rouf Mosque.

Architecture is a "social responsibility"

Tabassum grew up in Dhaka, Bangladesh, where she established her studio Marina Tabassum Architects (MTA), which she has led for the past 17 years.

Her childhood in the country has influenced her practice, with a number of her studio's projects aiming to create better homes and lives for people in Bangladesh, which has a high income inequality.

"I come from a country where I've grown up seeing this disparity between the rich and poor, and every single day when I get out of my house, you see this disparity," said Tabassum.

"I don't know about architects in other countries and how they should be doing it, but in my case, I encourage the younger generation of architects to come and work for the people who have no knowledge about architecture," she said.

"I think it's a social responsibility for us, especially in Bangladesh, where we can make our knowledge and our skills available to people which can really help better people's lives and living environment."

The Comfort Reverie building in Dhaka, where MTA is based. Photo is by FM Faruque Abdullah Shawon

The Comfort Reverie building in Dhaka, where MTA is based. Photo is by FM Faruque Abdullah Shawon

With her architecture, Tabassum aims to create appropriate buildings with "a sense of place", something she believes has been lost as architecture has become more homogenous over the past 30 years.

"Every place has a uniqueness that through an evolutionary process has come to a point where it's the geography, the climate, the history, everything comes together and creates something which is very essential of a place," Tabassum said.

"I think especially during the very high-flying capitalist time in the 1990s, and even in the 1980s, where we were just building profusely all over the world in this capitalist endeavour, we lost that idea of uniqueness," she added.

"We are losing the value of the uniqueness of a place"

Tabassum studied at the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology, at a school set up by the Texas A&M University, and graduated in the mid-90s – a time when, according to her, architecture was becoming increasingly homogenous.

"When I graduated from architecture in Dhaka, I saw the same thing," she said. "It's just stacks of floors, built very quickly – you just put glass on [buildings], everything is about aluminium and glass and that's it, the building is done. "

"It had no sense of the place and if you see the cities that were growing up during that time in China, or in the UAEs and the Arabian Peninsula, everything echoes that idea of globalisation, where everything is kind of standardised, fast-breed buildings," she added.

"To me, that really felt like we are losing the value of the uniqueness of a place."

Tabassum's Bait Ur Rouf Mosque is made from brick, a material traditionally used in Bangladesh. Photo is by Sandro Di Carlo Darsa

Tabassum's Bait Ur Rouf Mosque is made from brick, a material traditionally used in Bangladesh. Photo is by Sandro Di Carlo Darsa

Instead, Tabassum aimed to find her own voice by designing using local materials. Many of her projects, including the Bait Ur Rouf Mosque, are constructed from brick – a common material in Bangladesh.

"I have tended to work with brick because it works with the climate, it ages very gracefully, in my opinion," the architect said.

"Instead of let's say concrete, which is not that great and especially in our weather – we have so much rain that within a few years the concrete ages quite poorly. But brick ages quite beautifully."

"Glass is not able to take enormous heat"

As architecture has become more global, she believes that buildings have also become less adapted to local climates.

"We've always focused on the idea that the building must be climatically appropriate, so that it's not dependent on any kind of artificial means, like air conditioning, only," she said.

"Which you don't see anymore when you have glass buildings because glass is not able to take enormous heat – it just turns into a greenhouse," she added.

"That's what's wrong with the kind of architecture where you take something from a cold country and bring it to a warm country like ours."

The Khudi Bari lets owners sleep on a higher level when needed. Photo is by FM Faruque Abdullah Shawon

The Khudi Bari lets owners sleep on a higher level when needed. Photo is by FM Faruque Abdullah Shawon

Among the projects that Tabassum designed specifically for the Bangladeshi climate is Khudi Bari, modular houses that can be moved to help communities survive in Bangladesh's "waterscape," which is increasingly affected by flooding exacerbated by climate change.

"Khudi in Bengali means tiny and Bari is house, so these are really modular houses, especially for the landless," Tabassum explained.

"Bangladesh is all about water – it's a waterscape rather than landscape, there are so many different varieties of water bodies."

[

](https://www.dezeen.com/2021/11/18/marina-tabassum-wins-soane-medal-architecture-news/)

There are essentially two types of people affected by the flooding in Bangladesh, according to the architect – people whose land is periodically flooded during the rainy season, and people who are continuously on the move because the land is constantly shifting.

The Khudi Bari houses were designed to be of use to both groups.

"Each one is quite different so we're trying to give them different solutions to these kinds of houses," Tabassum said.

"We deliver a modular structure which has two levels, so if you have flooding you can move yourself to the upper deck and save yourself and when the water recedes you can start living your life," she added.

"When you have to move, this is a lightweight flatpack system that you can take down and it's very low-cost, it's about £300 all together."

The modular Khudi Bari houses were designed to be disassembled and moved. Photo is by Asif Salman

The modular Khudi Bari houses were designed to be disassembled and moved. Photo is by Asif Salman

The homes are built from bamboo and steel in order to make it as easy as possible for people to be able to source the materials and build the houses themselves.

Tabassum hopes to eventually be able to train steelworkers locally to make the steel joints needed for the building, which are currently supplied by the architects.

"We would like to make it in a way so that any steelworker in any location can make it," Tabassum said.

"But the rest of the material people source on their own so they can decide how big their house will be and what accessories it will have – there's a sense of ownership about it, which is important."

Designing for refugee camps requires understanding "definition of beauty"

As well as designing homes for those who have become displaced by flooding – a problem that is likely to increase as the climate crisis continues – Tabassum is also creating architecture for people who have been displaced from their country of origin.

Her studio is working with the World Food Programme to build food distribution centres in Bangladesh's Cox's Bazar refugee camps, which house Rohingya refugees from Myanmar.

Designing for the camps, where nearly one million people live, comes with its own unique difficulties and limitations.

"A lot of things are not allowed," Tabassum explained. "You are not allowed to use any permanent materials, everything has to be temporary."

The Baharchora Aggregation Center is one of the buildings created for the World Food Programme. Photo is by Asif Salman

The Baharchora Aggregation Center is one of the buildings created for the World Food Programme. Photo is by Asif Salman

"You cannot build anything beautiful," she added. "So being an architect, you deal with beauty and aesthetics in many ways – it's what we have been taught."

"And now to go against that and design something that is so-called not-beautiful is a challenge, you have to work around that, you need to understand the definition of beauty – what is beauty?"

To create beautiful and practical temporary buildings the studio worked with bamboo, rather than more permanent materials.

"You have a very limited palette of materials but you try to create something out of that," Tabassum said.

[

As Tabassum continues working on both her studio's regular projects – it is currently designing a hospital on the outskirts of Dhaka – and its designs for displaced people, she feels that people are at last taking action to help mitigate the climate crisis.

But above all, she believes there now needs to be a focus on collaboration.

"I think it's important to understand that we're living on one single planet, and the north and south are connected in every single way," she said.

"And the majority of the population of the world lives in the Global South. And so it is an enormous responsibility of the north and the south, equally, to come towards a resolution where it is about mitigating our existential crisis."

The main photograph is by Barry MacDonald.

The post "Wherever I work I must understand that place" says Marina Tabassum appeared first on Dezeen.

#all #interviews #architecture #marinatabassum #bangladesh #sustainablearchitecture #dhaka

RTÉ Six One interview with Russia’s Ambassador to Ireland Yuriy Filatov.

Some hard questioning of the Russian Embassador to Ireland ... for now.

Ad-infested surveillance-capitalism access: https://youtube.com/watch?v=xqx0m29WHIU

https://yewtu.be/watch?v=xqx0m29WHIU

#Russia #Ukraine #RTE #Ireland #Interviews

At just 32, the self-proclaimed "outspoken" historian Neal Shasore has become the head of the London School of Architecture. In this exclusive interview, he told Dezeen of his plans to make the school a beacon of inclusivity.

"Decarbonisation goes hand-in-hand with decolonising," said Shasore. "It means encouraging students to think about their projects in terms of sustainable and regenerative design solutions."

Shasore, who was appointed the London School of Architecture (LSA) head and chief executive officer in June 2021, believes that architecture education needs to respond better to today's social and political climate.

Changing with the times

He argues that "decolonising" the study of architecture – a contested term which broadly means separating it from the legacy of European colonialism – can pave the way for a more diverse industry.

"We need to look for radical territory and the new frontiers," the 32-year-old told Dezeen from the top floor of the LSA's east London base.

"Decolonialsim is an incredibly creative, stimulating and radical critique of the world," he added.

The LSA was founded in 2015 as an independent school of architecture – the first to open in England since the Architectural Association was established in 1847. Shasore is the first Black head of the school.

[

](https://www.dezeen.com/2021/03/02/london-school-architecture-neal-shasore-head-of-school-ceo/)

"One of the founding objectives of the school was to broaden access and make more affordable architectural education," said Shasore, who is a historian of Nigerian and Indian descent.

"But the LSA's vision was written before Black Lives Matter, before the declaration of a climate emergency, before Rhodes Must Fall and before George Floyd," he continued.

Shasore argues that the LSA's ethos must now adapt in line with recent political events such as the furore over the statue of 19th-century imperialist Cecil Rhodes and the wave of Black Lives Matter protests following the 2020 murder of African American George Floyd at the hands of police.

"I think that making more prominent those calls for racial equity and spatial justice need to be front and centre in that vision," he continued.

Racial reckoning in architecture

His call for such a shift comes at a moment of racial and social reckoning within the architecture industry.

Progressive steps such as Scottish-Ghanaian architect Lesley Lokko becoming the first Black architect to curate the Venice Architecture Biennale are broadening diversity within the field.

At the same time however, allegations of sexist and racist treatment in the industry have become more widespread, as in the case of The Bartlett School of Architecture.

The LSA provides students with a two-year postgraduate programme on subjects including designing cities and critical theory. In their second year, students embark on a practical course in which they are supported in seeking placements in London.

It has a reputation for taking an ambitious and innovative approach to teaching, with an emphasis on student empowerment.

"Diversity and inclusion is hard"

Shasore plans to use his previous experience as a visiting lecturer at the University of Cambridge's architecture school and as a course tutor for the MArch professional practice studio at the Royal College of Art to overcome some of the potential pitfalls that architecture institutions fall into when trying to become more inclusive.

"What I've learned over the last few years is you have to be in the room and you have to be outspoken," he said. "Sometimes that can be very uncomfortable."

"Diversity and inclusion is hard: it requires people to think harder, to be braver and to make less convenient decisions," he added.

Shasore cites listening to marginalised voices and broadening access to higher education as key ways to achieve "spatial justice".

He draws on his plans for fire and safety regulation training at the school, which will involve the 100 LSA students undergoing lessons about the Grenfell Tower fire as a more concrete example of how to decolonise education and the importance of recentering the voices of those who have historically been ignored.

[

](https://www.dezeen.com/2021/08/03/sound-advice-now-you-know-book/)

Grenfell Tower was a council-owned high-rise block in west London which was destroyed in a terrible blaze in 2017 as flames spread across its recently installed cladding system, claiming 72 lives.

A failure to listen to the voices of residents at Grenfell Tower − many of whom were from ethnic minority backgrounds − during its refurbishment has been repeatedly touted as a reason the building became so unsafe.

"One of the ways I would like us to teach that which is arguably quite technical and regulatory is not to lose that frame of the kind of broader picture of, in that case, racial and class inequality.

"The tragedy of Grenfell only reinforces that the ability to listen to and engage with diverse voices in the production of the built environment is vital," Shasore stressed.

Elsie Owusu, Doreen Lawrence, two recipients of the Open Up bursary and Neal Shasore

Elsie Owusu, Doreen Lawrence, two recipients of the Open Up bursary and Neal Shasore

Currently, he claims, "social housing, affordable housing is done onto people rather than enabling them to do for themselves."

As part of his plans for the school, Shasore also launched Open Up, a fundraising campaign designed to support prospective LSA students from underrepresented groups.

"We want to start to open up a conversation," he explained. "Open Up is also a call to action: it's a demand, as I see it, from those underrepresented groups, telling the professions to open up."

Campaign to support students from minority backgrounds

The Open Up campaign has already secured £30,000 from a collaboration with the Stephen Lawrence Day Foundation (SLDF) to develop a programme to combat the profession's "systemic barriers to diversity". Bursaries for two current students of colour have been funded using the money.

A recent partnership with the Zaha Hadid Foundation will provide a further two bursaries for prospective students from low-income backgrounds.

For Shasore, the collaboration with the SLDF holds great personal significance and as a consequence, he takes the responsibility to make it a success very seriously.

The SLDF foundation was set up in response to the racially motivated 1993 murder of Stephen Lawrence, a Black British teenager and budding architect.

[

](https://www.dezeen.com/2020/08/18/architecture-elitist-phineas-harper/)

"I feel privileged enough being appointed to run the school and even more privileged that one of the first big initiatives that I'm able to champion is in Stephen Lawrence's name," Shasore added. "That means something to a Black man."

Alongside the Open Up campaign, the LSA has recruited Afterparti's Thomas Aquilina to join the school in a special fellowship position called the Stephen Lawrence Day Foundation Fellow.

The role will see Aquilina lead the school's access and participation plan, including "conversations around curriculum reform", as well as providing a "visible role model" for students from underrepresented groups.

Shasore hopes that this approach will enable the school to become "a truly civic institution" with a focus on community-centric built environments.

The post Architecture education needs "decolonisation and decarbonisation" says London School of Architecture head Neal Shasore appeared first on Dezeen.

#all #architecture #interviews #education #architectureanddesigneducation #diversity #londonschoolofarchitecture

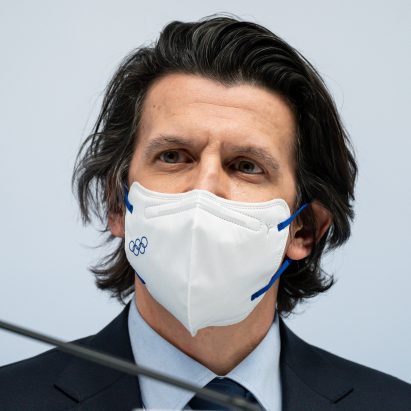

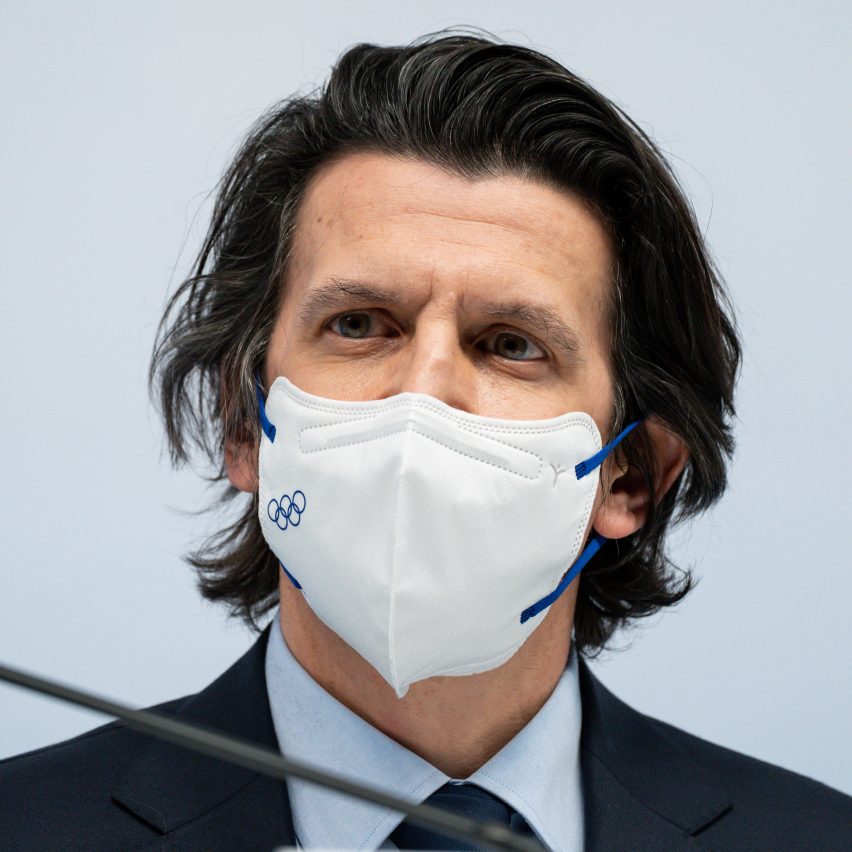

Few permanent buildings will be built for the Olympics in future, with events set to be hosted in existing structures and temporary venues instead, says Olympic Games executive director Christophe Dubi in this exclusive interview.

Building large numbers of new venues for the Olympic Games is a thing of the past, as organisers aim to limit the environmental impact of the global sporting events, Dubi said.

"The intention is to go where all the expertise and venues exist," he told Dezeen, speaking from Beijing.

Previously, host cities have commonly constructed several ambitious arenas and sports centres, taking the opportunity to exhibit their ability to undertake major infrastructure projects on a global stage.

But only a handful of venues were built for the ongoing Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, continuing a theme from other recent Games.

A long-track ice skating arena was designed by Populous and a pair of ski jumps were created, with the city reusing multiple venues built in the city for the 2008 Olympics.

"We don't want to force hosts into building venues"

This continues a strategy for reuse that saw many events at last year's Tokyo Olympics hosted in venues built for the 1964 Olympics. Dubi and the Olympic organisers will continue placing an emphasis on existing buildings at future games, he said.

"It simply makes sense because we have a pool of potential organisers that is finite," said Dubi, who is tasked with overseeing the delivery of the Olympics.

"So why don't we go to the regions that have organised the games in the past or have organised other multi-sports events, hosting world cups and world championships?" he continued.

"We don't want to force hosts into building venues that you're not certain you can reuse in the future."

No demand "for a crazy amount of new building"

While only a handful of venues were built for Beijing 2022, even fewer are set to be constructed for some of the upcoming Olympic Games.

Dubi explained that "only one new venue will be built" for the Milano Cortina Olympics in 2026, while "zero new venues" will be built for the Los Angeles Olympics in 2028.

Top: Christophe Dubi is the Olympic Games executive director. Photo by IOC/Greg Martins. Above: Big Air Shougang was one of the only venues built for the Beijing Winter Olympics. Photo by IOC

Top: Christophe Dubi is the Olympic Games executive director. Photo by IOC/Greg Martins. Above: Big Air Shougang was one of the only venues built for the Beijing Winter Olympics. Photo by IOC

Given the focus on reusing existing structures, Dubi doesn't believe that we will see Olympic parks full of new buildings, like those created for the Sochi, London, Athens and Sydney games, ever be built again.

"I don't think we'll see that [entire Olympic campuses built] in the foreseeable future," he said.

"The reason being, I don't think the expectations of a given community at this point in time, or in foreseeable future, is for a crazy amount of new building."

"Virtually any city can host the games"

Dubi argues that rather than limiting the number of cities able to host the games, focusing on existing venues combined with temporary structures can expand the number of potential host cities.

"We don't have a requirement to build anymore, so virtually any city can host the games," he argued.

He envisions host cities making use of temporary structures, like the volleyball venue on Horse Guards Parade at the London Olympics in 2012 or the skateboarding venue in the Place de la Concorde at Paris 2024, alongside existing permanent venues.

"What we will see is a crazy amount of [temporary] fields of play," he said.

"We'll see probably temporary stadiums of up to 40,000. So certainly more fields of play, more leisure opportunities for communities, but probably not a huge amount of new stadiums."

Dubi expects more temporary venues, like the Horse Guards Parade at the London Olympics. Photo by Ank Kumar

Dubi expects more temporary venues, like the Horse Guards Parade at the London Olympics. Photo by Ank Kumar

For specialist facilities such as ski jumps, he suggests that hosts could use venues in other cities or even other countries, citing the equestrian events at the Beijing 2008 Olympics, which were hosted in Hong Kong, and the surfing at Paris 2024, which will be hosted in French Polynesia.

"Say you're bidding for the games and you don't have a specific venue, we will simply say go elsewhere, it's going to be just fine," he explained.

"We have one currently in the south of Europe that is thinking about [hosting a Winter] Games – they don't have ski jump or a bobsled track."

Overall, Dubi expects future organisers to be innovative and incorporate a city's existing architecture into plans for the games.

"If in the future, instead of having a temporary wall for sports climbing that is made out of nothing, if we can use one of the buildings in the city, well, let's use it," he said.

"That's what we're going to be looking for from organisers: be original, innovate, use what you have, what defines you as a city, as a community."

Read on for the full interview with Dubi:

Christophe Dubi: My role is to oversee and hopefully contribute a bit to first, conceiving any addition of the games, and then up to the delivery and the learnings of every addition.

It's a continuous cycle of what you've learned and what you can embed in the next edition. I was in charge of the commission that did the evaluation of these games here seven years ago. So starting from very baby steps when you discuss the vision until it materialises and is being delivered, like, we are now in the trenches during operations time.

Tom Ravenscroft: What was the thinking behind choosing Beijing to host this edition of the Olympics?

Christophe Dubi: Three things. One, which is not linked to architecture is the development of winter sports and what it means for China and for the rest of the world. This was number one because in Asia we've been in Japan for winter, we've been in Korea for winter, never in China and the whole north of China is incredibly cold.

You have a very active winter sports movement with a lot of potential for development. So we saw that as one of the future legacies.

When it comes to architecture, we have a game in winter that could reuse some of the 2008 solutions. From an architectural standpoint, those landmarks, like the Bird's Nest and the Aquatic Centre, remain icons in sports and architecture in general.

The possibility to reuse them and more than a decade later is a sign that they were well designed, well built, and well maintained.

At the same time, we needed new venues because they simply didn't have them. A bob and luge track and sliding centre they did not have across China. They didn't have any ski jumps. They didn't have a long track for skating. They have plenty of ice rinks. They are great in figure skating and superb in short-track but not long-track.

Tom Ravenscroft: How have Olympic venues evolved since 2008 and what lessons have you learnt from previous games?

Christophe Dubi: I think it's a sign of the times. The games always adapt to society and we are a magnifying glass of society at any given point in time. Take the example of last summer where mental health came to the forefront because of a number of athletes speaking out, and they were incredibly brave in Tokyo.

Mental health for years is something that exists. But everybody was pretty shy to speak about, and you don't really want and suddenly, because of these athletes coming to the forefront, it becomes mainstream.

And I think it's the same for architecture, here you are in the 2000s, where it has to be to be big, it has to be spectacular. While in the 2020s, it has to be probably much more subdued. And it's very fitting in this context as well.

Where the president of the country is speaking about these games always said that, yes, they have to be perfectly organised games, but at the same time, they have to be somewhat modest with, with inverted commas, because what we said before simply the size and you know, more modest. Modest for China.

We see more green buildings, we see more flat roofs with gardens and now it's even against the walls and these are the kind of things that you see now across Europe, in Milano and elsewhere and for sure, you will have that as well the Olympic venues.

Tom Ravenscroft: So you're saying it's a reflection of society, but should the Olympics lead the conversation on architecture and sustainability?

Christophe Dubi: You cannot escape because when you have such a big platform you cannot shy away from your duties and responsibility.

You cannot remain outside of the public debate because if you don't lead on some of these issues, expectations will be placed on you and if you don't talk about it and be transparent about them someone will place words and intentions on this organisation.

So yes, the Olympic games have a duty to be at the forefront and there are many things that the organising committees and the IOC for that matter are doing. You know our headquarter was for a very long time on the number of standards including BREEAM and others, we were the top-notch administration building in the world. Now it's been two or three years so I don't know whether it's still the case. You see we cannot be third.

Tom Ravenscroft: With the architecture, is this the least number of venues that have been constructed for an Olympics?

Christophe Dubi: We are having the smallest in Milano Cortina, which are games for which only one new venue will be built. And it's a multi-sport venue in the south of Milan, which will be used for ice hockey, but other purposes afterward.

The intention is to go where all the expertise and venues exist.

It simply makes sense because we have a pool of potential organisers that is finite right? So why don't we go to the regions that have organized the games in the past or have organised other multi-sports events, hosting world cups and world championships.

We don't want to force regions into building venues that you're not certain you can reuse in the future.

A ski jump, unlike an ice rink, only ski jumpers can use. So you don't want to force a future host in 2030 or 2034 to build the venue if it's not absolutely needed for especially community purposes, you want to make sure that everything you do can be used by the top athletes, but also by the general public .

So say you're bidding for the games. And if you don't have a specific venue, we will simply say go elsewhere, it's going to be just fine.

We have one currently in the south of Europe that is thinking about games – they don't have a ski jump or a bobsled track.

In 2008 we organised the equestrian in Hong Kong, and it was okay. It was still the Beijing Games, but it was in Hong Kong.

Tom Ravenscroft: So you are looking for creative solutions. You don't expect cities to build every venue anymore. Do you think we'll ever see another Athens or Sydney where all the venues are built from scratch?

Christophe Dubi: I don't think we'll see that in the foreseeable future. And the reason being, I don't think the expectations of a given community at this point in time, right here right now, or in foreseeable future is for a crazy amount of new building.

What we will see is a crazy amount of fields of play, because leisure, especially leisure in urban environments is incredibly important.

We'll see probably temporary stadiums of up to 40,000. So certainly more fields of play more, more leisure opportunities for communities, but probably not a huge amount of new stadiums.

Tom Ravenscroft: Do you foresee an Olympics where nothing new is built?

Christophe Dubi: In Los Angeles, we will have zero new venues.

Tom Ravenscroft: Will that become the benchmark, where you really have to justify building anything?

Christophe Dubi: Let's look at it differently. If I asked you what are your best memories out of a given Olympic Games? Is it a visual imprint of a stadium? Or is it the emotion of an athlete's reaching out to another or a moment in an opening ceremony?

Our business is the business of emotions. And sometimes the visual impression helps. But the raw material, the most powerful one is the human.

We will still create incredibly powerful stories in any location when human beings are writing something special. Sometimes it can be the beauty of a segment of an opening ceremony. Sometimes it's on the field of play, others it can be volunteers, helping someone in the industry. And sometimes it is the Bird's Nest that radiates at night.

Tom Ravenscroft: So the architecture is a supporting actor?

Christophe Dubi: I wouldn't rank in this order, when I can say is that the first impression that, that you get entering the Bird's Nest in Beijing is that it is something special. And what happens here is bound to be special because this venue is in. So you know, I cannot say it's first or second. Yeah, it's all part is that you can create incredible things out of nothing.

But if you have something very special like that, for sure. It's very conducive to creating something special from the start. Everybody can just jump in quickly. I think everybody's entry point is different.

Tom Ravenscroft: So what will be the legacy of these games then? How will create a legacy in a city like LA when there aren't going to be any new buildings?

Christophe Dubi: Two things. The first is you create a physical legacy if it is needed. So if LA considers that they don't need new venues, and you have a sufficient number for the games, why create a legacy that is not helpful to again a community that's the main thing because you cannot now conceive the venue just for the sake of elite athletes, which is fantastic.

They inspire us, but at the same time, you have to make sure that you have greater use and the community so do not create something that is not needed. A venue like Horseguards Parade, which was a full temporary venue, does not have a lesser legacy in the mind of people that a newly built purpose venue.

Paris is a city where you don't want to build too much because you want to make sure that you use the city backdrop as your venue.

And building an urban park with skateboarders on Place de la Concorde, where you have, to your left, looking from the south you have on your left the Eiffel Tower, and on the other. It is a temporary venue that also will have a formidable legacy.

And it's all around the built environment, except that you don't deal new, using what is good, what is part of the history and the culture of that host community to make an impression and a legacy for you and for me, okay, so the approach,

Tom Ravenscroft: So the aim is to use the architecture without having to build new architecture?

Christophe Dubi: Correct. If in the future, instead of having a temporary wall for sports climbing that is made out of nothing, if we can use one of the buildings in the city, well, let's use it.

Okay, so that's what we're going to be looking for from organisers be original, innovative use, what you have, what defines you, as a city as a community. And let's create this together that visual impression that that souvenir that is set in stone.

We're not against building because Sochi is incredibly successful now winter and summer, because they needed to get some of the winter fans, not necessarily across in Switzerland and France, which is probably a bit of loss.

But to also stay in Russia, they didn't have any, any real great resort. Now they do have one and it's incredibly used. And it's the same here in China, it would have been wrong for us to say you're not allowed to build. But when you build it has to make sense.

Tom Ravenscroft: So not having a ski jump is not going to exclude you from hosting.

Christophe Dubi: Correct. If the Chinese would have said, by the way, we want to go elsewhere for the ski jumps we would have said, fine. Good. Tahiti will do surfing for Paris? Okay. Right. With the best wave in the world, most powerful.

Tom Ravenscroft: Do you ever see a point when one city will become the permanent host?

Christophe Dubi: No, because what makes this is the diversity. It's the inclusivity it's the arms wide open. It's games which are for everyone. What we were doing in having the games moving from one area to the other is to show how rich and diverse is the world. And our great it is when the world comes at one in one location,

Tom Ravenscroft: And how do you justify moving on a sustainability level?

Christophe Dubi: Because we don't have a requirement to build anymore, so virtually any city can host the games. And I dream to see the games coming to a continent that never hosted them. The first Youth Olympic Games will be in Dakar in 2026. And this is brilliant.

Tom Ravenscroft: Will there be a Winter Olympics in Africa?

Christophe Dubi: You could envisage one in the southern hemisphere, you could imagine Argentina, or actually New Zealand, it would just be a little bit of an upset to the calendar?

The post "We don't have a requirement to build anymore" says Olympic Games director appeared first on Dezeen.

Architect Stephen Slaughter was recently named as the chair of undergraduate architecture at the Pratt Institute. In this exclusive interview, he explains how he aims to bring his ethos of activism and inclusion to the school.

"Our student body is the most important thing and the change they can make in the profession," he told Dezeen. "The change they can make in the world is what I consider paramount."

As chair of the programme, Slaughter will lead the department of 180 faculty and 700 students as one of the most high-profile Black academics in US architectural education.

At the Pratt Institute School of Architecture, he aims to continue his work pushing for diversity, equity and inclusion [DEI], which has been a core element of his time in academia, he said.

"DEI has been an integral part of who I am," he explained.

"My role as an educator and my role as a private citizen, and my role as designer, has always been to leverage my talents and my position to somehow bring benefit and value through design to the community I'm a part of and represent," he continued.

"These are the things that I'd like to be able to impart on Pratt."

Change students can make is "paramount"

Slaughter, who will take up the role in July, currently teaches at the University of Kentucky and the University of Cincinnati, and formerly at the Pratt Institute, where he was a visiting professor on the Graduate Architecture and Urban Design (GAUD) program.

While Slaughter will be focused on helping to enact change within the school, he believes the greatest impact he can have is through the change his students can make.

"I am a servant of the institute, and I'm the servant of the students and the faculty," he said.

"It takes one's own activism to make change"

His community-focused work has seen him collaborate with not-for-profits including Watts House Project and Elementz Hip Hop Cultural Art Center and he hopes that graduates from the Pratt Institute will contribute to improving communities.

"Academia is part of a larger social, civic, societal, cultural system and I think the larger system has issues that hopefully, we as educators can address through the education of the next citizens," said Slaughter.

[

](https://www.dezeen.com/2021/03/30/moma-reconstructions-architecture-and-blackness-in-america/)

"It's a bigger problem than could be solved specifically through academia alone. It takes one's own activism to make change within culture and society," he continued.

"I hope that we'll be graduating smart, intelligent, caring, compassionate activist students."

"I'd like to have a Pratt grad building shiny new opera houses"

However, this does not mean that Slaughter expects all his students to end up designing solely community-focused projects. He hopes that graduates from the Pratt Institute will be able to bring his ethos of inclusivity to all projects they work on.

"I also like the idea that students will be interested in building the next shiny new opera house, it's just that that opera house will be different," he explained.

"I'd like to have a Pratt grad building shiny new opera houses and leveraging the experiences and the perspective to make that opera house inclusive and sustainable."

[

](https://www.dezeen.com/2021/11/29/first-500-website-black-women-architecture-tiara-hughes/)

Slaughter was previously diversity, equity, and inclusion coordinator for GAUD where he contributed to the Pratt's DEI strategic master plan. As head of the school's undergrad programme, Slaughter will have a key role in enacting many elements within the plan.

"One of the planks of the DEI strategic master plan is hiring and recruitment, as well as creating a welcoming environment," he said.

"These are the things I understand and want to set forward, as part of the mission for the school. And these are the things that I'll be following up on and expanding in my role as undergraduate chair."

"I was taught by a diverse array of professors"

Slaughter has a wide and geographically diverse career. A first-generation university graduate, he completed his undergraduate and masters at Ohio State University, where both his parents worked "as a way of affording me an education".

His experience at Ohio set the course for how he developed his career to focus on community and inclusion.

"I was taught by a diverse array of professors that influenced my opinion and my position in architecture today," he said.

[

](https://www.dezeen.com/2019/06/10/harriet-harriss-dean-pratt-institute-school-of-architecture/)

"Mabel Wilson, who's an amazing educator and writer was one of my professors, as were Jeff Kipnis, Peter Eisenman and Nathaniel Belcher," he added. "I had a wide variety of educators and academic perspectives."

From Ohio, Slaughter moved to California to work for Thom Mayne at Morphosis and lived in Los Angeles for several years, before returning to Columbus, Ohio, to help look after his sick father.

During this time he taught at the University of Cincinnati, which he said: "turned into a tenure track position and launched me as a dedicated educator".

"I feel like there's a commitment from the school"

Based in New York, the Pratt Institute is one of the best-known architecture schools in the US. It is led by British architect Harriet Harriss, who was made dean in 2019.

Slaughter took the role at the school as he believes that there is an appetite to tackle many of the issues surrounding the lack of diversity in both academia and the wider architectural profession.

"It's going to take commitment and I feel like there's a commitment from the school, from administration to the students," he said.

"Unfortunately, in both professional and academic career, I've been a part of more than a few initiatives that spin wheels and actually aren't interested in making a substantial difference," he continued.

"At Pratt, my colleagues in this effort were committed and that was the first time I've seen anything like that. It was more than invigorating to know that administration, staff, students, and faculty were committed."

In the US, as in many western countries, architecture is largely a white profession with Black architects making up only two per cent of the profession, compared to 14 per cent of the population.

American architect Tiara Hughes recently launched a website called First 500 to showcase the work of Black women architects working in the country.

The post "We'll be graduating smart, caring, compassionate activist students" says new head of Pratt undergrad programme appeared first on Dezeen.

#all #architecture #highlights #interviews #architectureanddesigneducation #prattinstitute #diversity

https://www.globalresearch.ca/documentary-film-planet-lockdown/5768063

" #PlanetLockdown is a 90-minute #documentary #film on the #situation the #world finds itself in. By watching all the #interviews, you will have the equivalent of a master’s degree on #current-events."

#planet #lockdown #courage #truth #law #justice #science #medicine #experiment #nuremberg-code #coup-détat #global #propaganda #fear #deception #police-state #civil-rights

https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/c/assange-integrity-and-courage

https://boutique.investigaction.net/fr/home/136-julian-assange-parle-karen-sharpe-9782930827933.html

“ #Assange has taken the side of the #victims against the powerful who #conspire against them in #secret” … #CharlesGlass

“Of all the #publications about #JulianAssange, this - #in-his-own-words, stands out as #eloquent and #powerful. It’s #Julian #speaking." … #JohnPilger

#helenmercer #book #review ’ #julianassange-in-his-own-words #french #julianassange-parle #collection #speeches #essays #interviews

#integrity #courage #philosophy #politics #karensharpe #wikileaks #freeassange #orbooks

https://youtu.be/8EsjVNbuNpI #Manifestation #Barcelone #Espagne #passe #sanitaire #1janvier #covid-19 #témoignages #interviews